Navajo Rugs, Part 1, Western Art Collector

By Medicine Man Gallery on

Collecting Navajo Rugs Part 1: History and Styles

Are you attracted to the exquisite beauty and craftsmanship of Navajo rugs but confused by all the terminology? To assist you, we asked expert, Dr. Mark Sublette, of Medicine Man Gallery, to provide a brief history of Navajo weaving.

by Dr. Mark Sublette

Reproduced courtesy of Western Art Collector magazine, February 2008

Dr. Mark Sublette, owner of Medicine Man Gallery, in the textile room at his gallery's Tucson, Arizona location. Photo by Meghann Eppstein

The Navajo (Dine (dih-NEH) in their own language) are Athabascan-speaking people who migrated to the Southwest from Canada in about the 15th century. Navajo women learned weaving in the mid-1600s from their Pueblo Indian neighbors who had been growing and weaving cotton since about 800 AD. Spanish settlers had brought their Churro sheep to the region in the early 1600s and introduced the Navajo to wool. By the early 1800s, Navajo weavers used wool exclusively, and became well known among both their Indian and Spanish neighbors for finely woven, nearly weatherproof blankets that became popular trade items.

Garments-especially wearing blankets-comprised most of the products of early Navajo looms. Traditional, Native-made blankets were wider than long (when the warp was held vertically) and were known as mantas. The Spanish introduced the longer than wide serape form that was easier to make on European-style looms. Mantas and serapes were generally used in the same way: wrapped around the shoulders with one long edge turned over as a "collar." However, mantas also were used by women as wrap-around dresses. Serapes only rarely had a slit in the middle for the head which made them ponchos. Navajo weavers made both the manta and serape styles during the eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries along with shirts, dresses, breechcloths, and sashes. These early weavings made before the 1870s are very rare, bringing tens of thousands of dollars-or more-from collectors and museums.

Navajo First Phase Chiefs Blanket Central Fragment, c. 1800, 16" x 54"

The so-called Chief's Blanket is a specific style of manta that went through a distinct design evolution.

-First Phase blankets were made from about 1800 to 1850 and consisted simply of brown (or blue) and white stripes with the top, bottom and center stripes usually being wider than the others.

-Second Phase blankets included small red rectangles at the center and ends of the darker stripes and were made about 1840 to 1870.

-The Third Phase type, between 1860 and 1880, saw the addition of stepped or serrated diamonds of color to the center and ends of the wide stripes.

-In weavings of the Fourth Phase, made from 1870 through the early 1900s, diamond motifs became larger and more elaborate, often overtaking the stripes as primary design elements.

Revivals of chief's blankets-usually made as rugs-have been popular since the 1950s.

Navajo Classic Serape, c. 1860, 73" x 52"

Navajo Classic Second Phase Chiefs Blanket, c. 1860, 56" x 73"

A watershed in Navajo weaving came in the 1860s with the incarceration of about 8000 men, women and children at Bosque Redondo reservation in eastern New Mexico. In an effort to subdue and "domesticate" the Indians, the US Army slaughtered the Navajo's sheep and destroyed their crops and homes. The government allowed weaving to continue during the internment by replacing the Navajo's home-grown wool with factory-made yarns from Europe and the eastern United States. After the Navajo returned to their homelands in 1868, the US government continued to provide commercial yarns as part of their "annuity" support for the Navajo people. In the 1870s, licensed Indian Traders began supplying weavers with factory-made yarns brightly colored with aniline (chemical) dyes. Blankets made of these colorful yarns are generically called Germantown weavings after the town in Pennsylvania where much of the yarn was produced. The use of Germantown-type yarns ceased shortly after 1900.

Navajo Child's Blanket, c. 1870, 53" x 35"

Navajo Third Phase Chiefs Blanket Variant, c. 1870-80, 59" x 65"

Transitional weavings

The Navajo returned from Bosque Redondo to a very different world; one increasingly tied to the larger Anglo-American economy and culture. Families quickly rebuilt their sheep herds and resumed production of their own hand-spun yarns, although the Churro sheep had been replaced by American Merino sheep which had shorter, greasier wool that was much harder to clean and spin by hand. Weavers also found that the market for their blankets was changing rapidly. The trading post system and its ties to the railroad brought relatively cheap manufactured clothing and supplies to the Navajo and surrounding tribes. Anglo-style coats and dresses were replacing wearing blankets as the clothing of choice among Native peoples.

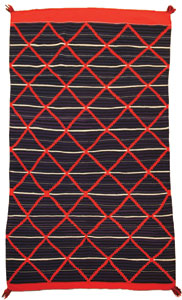

Navajo Germantown Moki, c. 1890, 79" x 48"

Increased difficulty and declining demand took its toll on both the weavers and their product. During the last two decades of the 19th century, most Navajo blankets were woven of spongy, loosely spun yarns most frequently dyed with aniline reds, oranges and yellows. Beside the chief's blanket mantas, two types of serape blankets predominated in this period. Banded Blankets made with simple stripes of contrasting color were descendants of the earliest Navajo weavings.

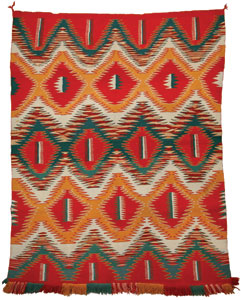

Navajo Germantown Eyedazzler, c. 1890, 71" x 57"

A more complicated type of design was derived from Hispanic Saltillo serapes which featured brightly colored patterns of serrated diamond shapes. Weavers frequently outlined the small serrated patterns with a single yarn of contrasting color to heighten the visual complexity and impact. This patterning technique became known as the Eyedazzler and continues to be popular to the present day. Both the banded and diamond pattern homespun blankets of the late 19th century are generically known as Transitional Blankets because they signaled the end of Navajo blanket production and ushered in the era of the Navajo rug.

By the 1890s, the internal demand for Navajo weaving was almost non-existent. To make matters worse a widespread financial panic seized the US economy in 1893, depressing commodity prices for the raw wool that had come to replace weavings as the Navajo's primary trade item.

Navajo Double Saddle Blanket, c. 1915, 50" x 35"

During this difficult time, several traders realized that there could be an external market for Navajo weavings made as rugs rather than blankets. The nascent market for Indian rugs was fueled at the turn of the century by a growing national interest in Native peoples and artifacts. Well-heeled tourists to the Southwest wanted unique souvenirs of the exotic places and peoples they visited, and rugs could easily be incorporated into the highly eclectic and overstuffed interiors of the period.

Navajo Ganado rug, c. 1920, 70" x 46"

The rug market was not limited to tourists, however. Many people who would never visit the Reservation appreciated the exotic designs and laborious handcraftsmanship of Navajo weaving. Proponents of the Arts & Crafts design movement found that the bold, geometric designs harmonized beautifully with their simple furniture and handmade accessories. By 1896, C.N. Cotton, a trader in Gallup, New Mexico had issued a catalogue in an effort to expand his market to eastern retailers. Other traders, most notably Lorenzo Hubbell at Ganado, Arizona and J.B. Moore at Crystal, New Mexico, followed up with their own catalogues in the early years of the new century, focusing specifically on rugs. Navajo weaving had quickly gained a national audience.

Navajo Klagetoh textile, c. 1920, 79" x 48"

From the 1880s through the 1930s, reservation traders were the Navajos' primary contact with the outside world. As such, they also were the weavers' primary - or even sole - customers. Therefore traders exercised significant influence on weavings simply by paying more for the designs, sizes, colors, and qualities they wanted. Of course, traders' choices were driven by what they thought they could sell to their off-reservation customers, but they also were guided by their own aesthetic sensibilities. As a result, distinctive styles of rugs emerged around several trading posts in the first years of the twentieth century. Such combinations of pattern and color are known as Regional Styles and are typically named after the trading post that encouraged their production.

It should be noted, however, that many rugs produced throughout the century did not conform to a particular regional style and are now difficult to assign to a specific trading post. In recent years as weavers have become more mobile and independent of local trading posts, they often choose to weave patterns originated outside of their area. Many also combine motifs and characteristics from several different regions. As a result, the regional style names are now mostly used to identify common pattern types without necessarily referring to the exact place of origin of a specific weaving.

Navajo Crystal textile, c. 1910, 95" x 54"

Influential Traders

Juan Lorenzo Hubbell was, by most accounts, the leading trader of the early period in rug-making, and owned several trading posts around the Reservation. Hubbell's home and base of operation were at Ganado, Arizona about 50 miles south of Canyon de Chelly. His tastes ran to Classic Period weavings and many of the early rugs made by Ganado area weavers were close enough in appearance to classic mantas and serapes to have earned the generic name, Hubbell Revival rugs. Hubbell guided his weavers by displaying paintings of rug patterns he favored. Many of these paintings can still be seen at the original trading post, now preserved and operated as a National Historic Site.

Hubbell preferred a color scheme of red, white, and black, with natural greys. By the 1930s, Ganado area weavers had thoroughly adopted the color scheme, but had moved away from Classic-inspired weavings to new patterns with a large central motif-often a complicated diamond or lozenge shape-with a double or triple geometric border. These rugs frequently had a deep red "ground" or field on which the central motif was superimposed, and are now known as the Ganado regional style. Weavers around the nearby trading post at Klagetoh, Arizona (also owned by Hubbell) often worked in the same colors and patterns, but reversed the color scheme and used a grey ground with red, white and black central motifs. The Ganado and Klagetoh style rugs continue to be made to this day and are among the most popular of all Navajo rug designs.

Navajo Crystal Storm Pattern with Whirling Logs, Waterbug, and Arrow motifs, c. 1920, 86" x 56"

J.B. Moore, who owned the trading post at Crystal, New Mexico from 1897-1911, was another visionary trader who exercised enormous influence over early Navajo rug design. Perhaps his most important innovation was to introduce weavers in his region to Oriental rug patterns. Rather than copying wholesale, the Navajo filtered the new patterns through their own cultural sensibilities and personal design preferences. In the process, they drew out specific concepts and motifs, re-synthesizing them into distinctly Navajo designs.

Motifs probably derived from oriental rugs include repeated hook shapes (often called "latch hooks"), the "waterbug" shaped like an "X" with a bar through the middle, the "airplane" or T-shape with rounded ends and, in a small number of weavings, rosettes. An even more lasting and fundamental influence was the concept of a large central motif in one, two or three parts that covers almost all of the ground between the borders. Even the concept of the border itself, usually in two or three layers with at least one in a geometric pattern, is probably traceable to oriental carpet design. Though introduced in the regional around Crystal, these motifs and ideas quickly spread to other areas of the Reservation and are found on many rugs woven throughout the past century.

Won first price at the 1957 International Indian Ceremonial in Gallup, New Mexico.

Moore's influence on Navajo rugs was not only widespread but of long duration. Designs his weavers developed before 1911 were still being made, virtually unchanged, as late as the 1950s. These oriental-influenced patterns are now known as Early Crystal rugs. Those made at the beginning of the century typically featured aniline red with natural whites, browns and greys, while rugs made from the 1920s on tended to rely even more heavily on a wide range of natural wool colors.

One of the most popular designs that likely resulted from Moore's work at Crystal was the Storm Pattern. It is generally defined as a central rectangle connected by zig-zag lines to smaller rectangles in each corner. The storm pattern often is said to have symbolic meaning: the zig-zags are lighting, the corner rectangles are the four sacred mountains of the Navajo or the four directions or the four winds, etc. Nevertheless, the great variety of interpretations suggests that meanings were assigned by traders and collectors, not by the Navajo themselves. The storm pattern's precise origin is uncertain-one story suggests it was developed by a trader on the western side of the Reservation-but the weavers at Crystal developed this concept into one of the most popular and lasting of all Navajo rug patterns.

Not far from Crystal was the Two Grey Hills trading post, known for weavings in which no dyes were used. Instead, weavers carefully combed and spun different natural colors of yarn to yield a beautiful range of creamy whites, tans, browns, and greys. (To get a solid black color, weavers sometimes would overdye dark brown wool with black dye.) The weavers around Two Grey Hills developed very complex geometric patterns, usually based on a large, hooked central diamond with multiple geometric borders. They also were known for very finely spun wool of small diameter which they used to make very thin, dense, and tightly woven rugs that are certainly the greatest technical achievements in the history of Navajo rug making. Many of the women who weave for nearby Taodlena Trading Post carry on this tradition of quality. The most finely woven rugs are often called tapestry rugs.

To further help you know what you are looking for when collecting Navajo Rugs, in Part 2, we will examine the 1920s revival and the emergence of the creative pictorial rugs that used a wide palette of newly developed dye colors.