Under the Rainbow - Navajo Germantown Weavings

By Medicine Man Gallery on

Under the Rainbow - Navajo Germantown Weavings

by Mark Sublette

All images courtesy of Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, AZ, and Santa Fe, NM

Courtesy Native American Art, June/July 2016

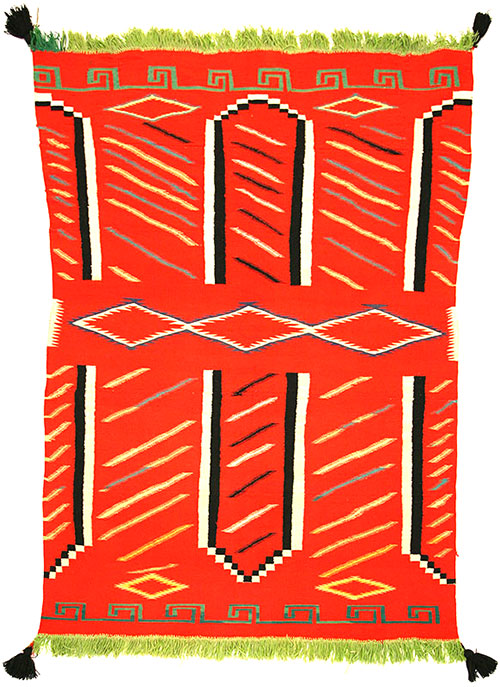

Navajo Third Phase Germantown chief's blanket, ca. 1890, 48" x 73-1/2"

Navajo blankets in the 1800s were prized not only for beauty, but also functionality. Plains Indians coveted these wider-than-long striped blankets, so-called chief’s blankets. Several horses could be traded to obtain a single Navajo serape, which might take the Navajo weaver a year to produce. The textiles were often tight enough to repel water with a design sense toward simplicity. Weavings from this classic time frame, pre-1865, have brought as much as $1.8 million at auction.

Blankets from this early period were produced using handspun yarn, natural dyes of indigo blue, and commercial trade cloth known as bayeta, employing red lac and cochineal insect dyes against backgrounds of white and brown. The handspun yarn was luxurious long staple Churro wool.

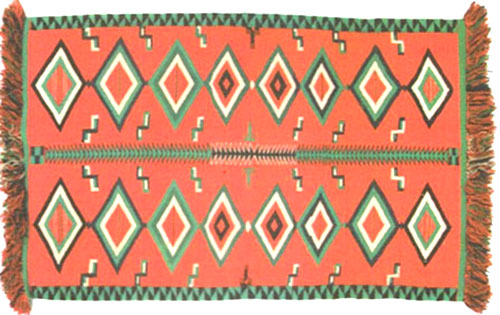

Navajo Germantown Banket, ca. 1890, 30" x 49" Navajo Germantown blanket, circa 1890, in excellent condition, descended from the original family that owned the Curry Mercantile Trading Post in Ouray, Utah. This piece was collected directly from its Navajo makers and put away. The dimensions are of a smaller size, 30 inches by 49 inches, and are often deemed a child’s blanket by dealers, but were more than likely made as a smaller example of a full-sized blanket, a more affordable and easier size to carry home on the train.

The use of natural dyes and handspun wool were the mainstay through the 1870s, after which red dyes were switched to aniline or coal tar dye. The first known aniline example is a Navajo Blanket owned by Chief White Antelope, collected at the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Accurate dating of early blankets includes yarn and dye analysis.

In 1868, three-ply commercial yarns were being produced by woolen mills around Germantown, Pennsylvania, and shipped to the Navajo reservation for use in weavings. By 1870, a four-ply yarn became the mainstay, which produced a very consistent even weave and came in a variety of bright aniline colors. These colorful, tight, well-composed Navajo textiles became known collectively as Germantown blankets. The majority of these Germantown weavings were composed of four-ply commercial wool yarn, which often used a cotton warp as their foundation, though the Ganado trading post owner John Lorenzo Hubbell discouraged the practice of cotton warps as they did not wear as well as those with a wool warp.

Navajo Germantown Eyedazzler Blanket, c. 1890, 77-1/2" x 54-1/2"

Early enthusiasts of Navajo blankets, including such well-respected collectors as the publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst, would pay $1,500 in 1900 for a great example. Famed American artist Maynard Dixon not only purchased Navajo weavings for his own collection, but acted a Hubbell’s agent in San Francisco, selling expensive pieces to art collectors. On April 19, 1906, Dixon did a self-portrait of himself, Fire and Earthquake, that shows him running from his studio after the great earthquake and fire clutching prized blankets and letting his oil paintings go up in smoke.

Maynard Dixon, Fire and Earthquake, 1906, Pen and Ink on Paper, 5" x 4"

Maynard Dixon, Fire and Earthquake, 1906, Pen and Ink on Paper, 5" x 4"

Most Germantown weavings were produced during the transitional period of Navajo weaving and date from 1880 to 1910; however, the majority were produced during the 1890s and made for trade or sale. The Navajo Germantown blanket, circa 1898, is an example collected on June 25, 1898 at Fort Wingate by a colonel in the 9th Cavalry. May early Navajo blankets have collection documentation from military officers. Often these weavings remain in excellent condition as they were expensive at the time and subsequently treated as special pieces by the families that owned them.

The Germantown weavings continue as they did in the 1890s to be a highly collectable art form, not only by textile collectors, but by the art world in general. Under the Rainbow, an exhibit and sale, runs from June 10 through August 23 at Medicine Man Gallery, 602 Canyon Road in Santa Fe. It brings together some of the finest Navajo Germantown textile examples produced from 1880 to 1920.

The classic example of Germantown weaving – the Navajo Germantown Eyedazzler blanket, circa 1890 – is done in an eye dazzler pattern. This term refers to Navajo weavings (usually Germantown yarns) that use all the colors of the rainbow and often have a zigzag-serrated design that leaves the viewer with a visual nystagmus of pulsating color. These amazing works of art required a patient master weaver. The abundance of color that was available in Germantown yarn led to an explosion of artistic expression.

Navajo Germantown blanket, ca. 1893, 58" x 34"

Often the ends in Germantown weavings had colorful fringe applied after the completion of the weaving, as in Navajo Germantown blanket, circa 1900. This added decoration is not commonly seen in any other weavings that the Navajos produced and serves as a good marker of a Germantown weaving. It is not to be confused with Mexican weavings that often had their warp ends showing.

Navajo Germantown blanket, ca. 1900, 79-1/2" x 50"

Germantown weavings also copied the earlier classic blanket designs of chief’s blankets. The Navajo Third Phase Germantown Chief’s blanket, c. 1890, is an example of a third phase chief’s blanket layout constructed from Germantown yarn.