Oreland C. Joe, CA Wildlife Art July/August 2007

Click to view available sculptures by Oreland Joe

Oreland C. Joe: Stone flows in his hands by Michael Scott Blair

Reproduced courtesy of Wildlife Art magazine, July / August 2007

Images courtesy of Oreland Joe, CA. Photos by Dale W. Anderson

“I used to wonder how the stone could be sculpted—it is so hard, so hard. But as technique and approach improve, the stone becomes fluid.” - Oreland C. Joe

Shiprock, the towering 40 million-year-old remains of an extinct volcano, roars up precipitously to nearly 1,800 feet above the desert floor just south of the Four Corners area of New Mexico, not too many miles from the town of Shiprock, where noted sculptor Oreland C. Joe was born on June 3, 1958. And though most of his work celebrates his Native American culture, which is deeply rooted in the sands of his birthplace, Joe has traveled the world studying techniques of sculpting, both ancient and modern, and he draws a clear distinction between art and culture—any culture.

Oreland Joe, Buffalo Sunrise, Portuguese Marble, 49" x 21.5" x 15". Won the Purchase Award at the 2006 Prix de West, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

“Art is art, and it transcends culture. Like music, it speaks to everyone who is open to its message,” he says. From early Greece and Rome, to Europe’s Renaissance and Baroque periods, to modern Japanese works, Joe has studied texture, form, mass and detail, and brought that learning back to his studio, where he creates pieces that have won some of the nation’s top honors.

Art in many forms has been a part of Joe’s life for as long as he can remember. His grandfather performed many of the spiritual songs and dances at traditional ceremonies. His Navajo mother not only has musical talent, but works with silver and precious stones. His Ute father, who died in 1976, was a truck driver by trade, but was skilled in working with leather and silver and as a painter, and, says Joe, all his family members have enthusiastically encouraged his artistic talents since he was 4 years old. “There was never any question that art was going to be my life. After all, I was selling pieces by the time I was 12."

Oreland Joe, Chief of the Capote, Marble, 30" x 13" x 10"

Changed by Europe

The wider world of art and sculpture opened for Joe when, as a 20-year-old, he was performing as a hoop dancer in Europe as part of a cultural exchange program. There, he got a firsthand introduction to the breadth of sculpture in the Louvre Museum in Paris and at the Palace of Versailles, and hurried home to fashion his works in the unforgiving medium of stone.

To Joe, sculpture, especially stone figures, were very rigid for centuries. Limited movement was introduced, but it was not, Joe says, until the Renaissance period (generally accepted as starting in Florence and lasting from the 14th to the 17th centuries) and the 16th century Baroque period, which started in Rome, that movement appeared in sculpture. “I think it was Michelangelo (Italian, 1475-1564) who really brought the sculptured body to life.

Oreland Joe, Piegan Ritual, Marble, 31" x 20" x 17"

“To me, perhaps Antonio Canova (Italian neoclassical sculptor, 1757-1822) was the most influential. One day, I was looking at one of his works in Lake Como in Italy, and I remember wondering whether I would ever be able to carve sandals like he did, or the shoe laces with designs on them,” says Joe. “It was not just the detail I was looking at, but the whole thing—the mass, the gestures, etc., but once you have that, you move on to the details of the hands, the fingernails, the nose. “I’m not limiting myself to that kind of art. I do pieces that are either very simple or that depict extreme realism. At present, I don’t seem to be able to fit in between somewhere. It is either one or the other. I love texture and softness. Sometimes I am caught in a museum, looking at a painting sideways because I want to see the texture by understanding how the artist laid the paint on the canvas,” says Joe. “Many things are very interesting when seen from a perspective other than head-on—concrete, limestone, a city sidewalk—anything with texture is appealing to me.”

Oreland Joe, Dances of Summer, Indian Limestone, 31" x 21" x 13"

Joe is seeking to sustain and expand the skills of the Indian peoples in working with stone. “It is a difficult and unforgiving medium that does not attract a lot of people,” he says, and it is relatively new among Indian artists. Though “stone has been around for a long time and people have carved it for ages,” Joe says that Indian involvement with it as an art is generally attributed to having started with Allan Houser in the late 1940s. (Houser, 1914-1994, was an Apache sculptor from Oklahoma who became a Guggenheim Fellow and a recipient of the National Medal of Arts. His first stone piece was Comrades in Mourning, a 1948 Carrara marble tribute to young Indian students from the Haskell Institute in Kansas who died in World War II.)

Group Promotes Indigenous Sculptors

In the fall of 2000, a group of seven indigenous stone sculptors, all respected in their profession, came together for a weeklong symposium on marble carving at Joe’s studio in Kirtland, just west of Farmington, N.M. At the end, they formed the Native American Sculpture Society, now known as the Indigenous Sculpture Society, with the goal “to sustain and promote Native American stone sculpture.” The seven were Joe, Cliff Fragua, Kathy Whitman, Alvin Marshall, Rick Nez, Evelyn Fredericks and Tim Washburn. Two more members have been added since—Adrian Wall and Jon De Celles.

Oreland Joe and Chief Standing Bear, Bronze, 22 feet tall, Ponca City, OK

Large figurative pieces did not appear among the work of Indian artists until the 1960s and had really caught on by 1980, Joe says. Unfortunately, traders moved in and did not take the art very seriously. But when leading shows and top galleries started featuring Indian sculptors, it was clear that the genre was firmly established in the fine arts, he says.

Joe, himself, has had remarkable recognition at top shows. He received the 2006 Prix de West Purchase Award at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, and is a three-time winner of the sculptor’s award at the Autry Museum’s Masters of the American West. In 1993 Joe became the first Indian artist to become a member of the prestigious Cowboy Artists of America (CAA), and has won three gold medals for sculpture at the annual CAA shows. In 1996 he was chosen from 50 artists for a commission by the Ponca City Native American Foundation to create a 22-foot-tall bronze sculpture of Chief Standing Bear, which now stands in that Oklahoma city.

Oreland Joe, Whirlwind, Bronze, 24" x 14" x 14"

A father, with six children aged 14 to 26, Joe agrees that it is difficult for young sculptors to get instruction, which is just one reason for the creation of the Indigenous Sculpture Society. In his youth, he would wait months to attend a one-week intensive class at the Scottsdale Artists’ School, carefully planning exactly what he wanted to focus on improving before attending the class.

Good drawing is fundamental to quality art but many young artists fall short, he says. “A lot of young artists see themselves as hot, and they sell a lot, but they cannot get into the leading shows and they wonder why. The problem is that many of them cannot draw, and therefore, cannot form a well-sculpted feature,” says Joe. “The people jurying leading shows want to know if you can draw a hand, and rightly so. The trouble is that a lot of people can’t, and that is made worse by the fact that there are very few places to go to learn.”

Stone Reads Your Mood

Though stone is considered to be very hard, it is “almost human-like, almost alive, and sensitive to your moods,” Joe says. “If you come to work in the morning and you are calm and at peace, the stone will work with you. If you have a little itch up your neck or whatever, the stone is resistant. You are not in tune with everything that day, and the stone does not respond. I used to wonder how the stone could be sculpted—it is so hard, so hard. But as technique and approach improve, the stone becomes fluid, like water; it becomes transparent, and the artist is able to speak through the stone, seeing the beauty.

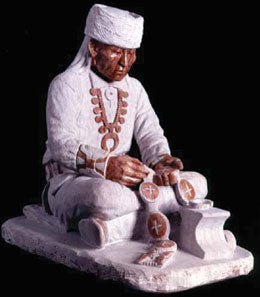

Oreland Joe, Final Touches, Alabaster, 20" x 20" x 12"

“Sculpture is very demanding—there are no shortcuts. Some two-dimensional painters can speed the process through projectors and such aids, but a sculptor would need 200 or 300 projections from every angle and perspective just to cover a figure’s foot—that just won’t work. When I think about it, for an artist to take a piece of stone from concept to finished item and not make a mistake or break it, is truly an accomplishment.”

Almost all of Joe’s ideas for pieces come from his native Indian culture, which presents an endless array of subject matter,” he says. First, there is technique, but “It is just technique, and I don’t care where I learn it or where I am trained. It becomes individual eventually because I learn from so many different places and people. I am curious about tools; I am curious about texture, polished areas or matte. I have learned from so many different people and sources that race or culture have nothing to do with it. So, first is tools and technique. Second is learning to draw. I cannot stress that enough. I am a realist; I am a figurative artist. If I draw a hand or an ear, that is what I want to create.

“But third, is the ideas, and as I have said, 100 percent of my ideas come from my culture. If the piece is to be about an aspect of my culture, I have a clear advantage over anyone not of my culture because I have lived and experienced it. Every piece has a message and those who have not studied my culture will not get 100 percent of the message. It is those who have dedicated time to knowing our culture that get the message—people like (Arizona artist) Howard Terpning, who thinks like an Indian,” Joe says. “His recent piece, The Shaman and His Magic Feathers, (unveiled earlier this year at the Autry Museum show and shown on page 32 of the May/June issue of Wildlife Art) is a remarkable example of his intuitive understanding of the Indian mind. I can talk with him about a lot of things that I cannot talk to anyone else about. He is one I can talk straight to and know that we see eye to eye.”

Shiprock, Oil, 22" x 30" One of the last paintings done by Oreland Joe's father, Ireland C. Joe, before his death in 1976 at age 36.

Uses Art to Teach Indian Culture

Joe looks to the future in two directions: first, to do more large-scale works, and second, to expand on his pieces that help young Indians understand and be proud of their culture and history. “There is a revival going on, not just in our language and not just among our own people, but about many parts of our culture and before a much broader audience. Right now it is a media culture, especially for young kids, with everything on television. Many younger people are very visual; they have to see it to understand, so I visit a lot of schools and I have some specific pieces to teach them about symbolic things in the culture, such as medicine bags and other ceremonial symbols. Hopefully, those pieces will still be around 50 or more years from now, helping young people stay in touch with the wonders and beauty of their culture.”

Oreland Joe, Shush, Bronze, 21" x 24" x 7.5"

Not far from his Kirtland studio, Shiprock pushes its craggy shoulders into the evening sky. It was called the Needle until the 1870s, when cartographers renamed it Shiprock because they felt its shape reminded them of the 19th century high-speed clipper ships that plied the world’s trade routes. But long before the clipper ships were ever dreamed of, the Navajo and other native peoples knew the history of the huge rocky outcropping:

A very long time ago, the Navajo were hard-pressed by their enemies. One night their medicine men prayed for deliverance and, hearing their prayers, the gods lifted the ground and the people on it (on the back of a bird in some accounts), moving it east, away from their enemies to where it rests today. These Navajos lived on top of the new mountain, going down each day to tend their fields and to get water. But one day, while the men were working the fields, the trail up the rock wall was split off by lightning and only a sheer cliff remained. The women, children and old men on the top slowly starved to death, leaving their bodies to settle there.

Asked if he and a non-Indian might do a similar rendering of Shiprock, Joe smiled gently and slowly shook his head. “No,” he said, “the other artist would see it with his eyes. I would hear it with my heart.” Most likely it is those long-lost souls atop the rock that speak so clearly to the heart of Oreland C. Joe.

Oreland Joe, Bluebird, Bronze, 39" x 14" x 8"