Star Liana York, Cowboys and Indians 2012

Star Liana York

Inspired by the figures and wildlife of the American frontier, the acclaimed artist decorates galleries and homes throughout the West with her spirited sculptures.

By Allyn Hulteng

Photography by Daniel Nadelbach

Styling by Gilda Meyer-Neihof

Published online courtesy Cowboys and Indians, June 2012

Lying on the grass, a mother bobcat keeps a careful eye on her three kittens as they playfully pounce on one another. A short distance away stands the tom, his eyes fixed on the female and her spirited offspring. The she-cat is well aware of his presence – and the fact that a human is watching, too.

Sculptor Star Liana York often ventures out to the New Mexico desert to observe her wildlife subjects in their environs. Never intrusive, she keeps her distance, and over time the animals have grown accustomed to her presence. This particular day, York focuses on the male bobcat, observing that he poses no threat to the female or her kittens. His face seems to radiate a watchful, even protective countenance.

“Most people don’t expect to see playfulness and nurturing in wild animals, but it’s there if you take time to look,” says York. It’s that spirit, the individual personalities of my subjects, that inspires my art.”

A native of Maryland, York was interested in art from a young age. Her father, an avid woodworker, had a shop in his basement where she spent countless hours cutting animals out of wood using a jigsaw and then painting them. But it was her high school art teacher who started York on the path to sculpting.

“My teacher taught me how to use a centrifugal caster to cast miniature sculptures,” York says. “I was completely captivated by the medium.” The teacher was so impressed by the young artist’s work that he entered the sculptures in an art show, which she won. “The owner of an art gallery in Chevy Chase [Maryland] saw my work at the show and asked to sell my pieces,” York says. It was a happenstance that set the course for her life’s work.

Gaining formal training in college, the aspiring artist continued to make miniature sculptures until she was commissioned to create a much larger bronze. “The sculpture was of an Anasazi medicine man making a sand painting,” York recalls. “I wanted his look of concentration to be rich with the subtleties of facial expression.” Such intricate detail wasn’t possible on miniatures. When York stepped back to look at the finished lifelike bronze, she realized, “Wow, I now know what I want to do with my art.”

York – who since getting her first horse as a teenager has been an accomplished rider and barrel racer – was always intrigued by the American West, and it was he passion for horses and the Western lifestyle that led her to focus on the people of the frontier as the prominent subjects of her art. “I wanted to explore the Western idiom in my work,” explains York. “The Old West is part of the identity of so many Americans.”

She began by recreating the first cowboys and Native Americans, including a bronze of a Pony Express mail hand-off titled Postal Exchange that won best of show in the National Sculpture Society. But many of her Western works also incorporate contemporary elements. Spring, the first in a series of four pieces that explore the different seasons of life, depicts a Navajo girl in traditional dress and jewelry with a pair of bright red tennis shoes subtly peeking out from under her skirt.

To produce her larger pieces, York needed a foundry that could accommodate her work. Finding none in the East, she eventually partnered with Weston Foundry in Santa Fe. Two years and several trips later, York permanently relocated to New Mexico, making her home on Pair O’ Dice Ranch along the Chama River with her husband, Jeff Brock, their horses dogs, and a menagerie of animals both tame and wild. “We have found the ranch life very rich and rewarding on many levels,” says the artist. “Raising and training horses helps us stay connected to the natural world, and regularly riding through such extraordinary scenic beauty if continually inspiring.”

York spent endless hours studying the animals’ antics, noting “their individual personalities and the character behind their eyes.” And though up until then her work had focused on characters of the Old West, York decided to try her hand at sculpting the wildlife she had been so keenly observing. “I didn’t want to sacrifice individuality for total authenticity, so I approached this work with a different style,” she says. “I use my artistry to express the animal’s personality primarily through the eyes and face.”

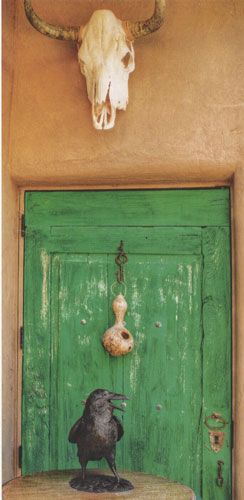

One of her first animal subjects was the bobcat. “I had observed a male bobcat in the wild seemingly watching over his mater and her litter,” says York, who captured the animal’s confident and relaxed look in a bronze called Guard Duty that now permanently resides, along with a handful of York’s works, in the home of a Santa Fe collector. Employing the same technique, York studied a host of other animals – horses, elk, mountain lions, and birds, like the chattering raven depicted in Palaver – learning their unique expressions and translating them into powerfully emotive sculptures.

Then her art took yet another turn when she traveled to France to study Paleolithic cave drawings dating back between 20,000 and 30,000 years. Well-preserved paintings rendered using red oxide, ocher, ad charcoal served as inspiration for a new series, including the equine sculptures Mares of the Ice Age. “The horses appeared chunky, voluptuous, and full of energy, representing abundance to Paleolithic man,” York notes. “They were so raw and beautiful. I worked to capture that essence in bronze using the same color palette and patina.”

Not one to be branded, York is known as much for the compelling nature of her sculptures as for the variety of styles and subjects she takes on. “It is so important to try and leave yourself open and to listen to your subconscious and do things you care about on a very deep level,” she says. “Those voices make a difference in understanding your personal uniqueness, and in that uniqueness you’ll find your art.”