Star Liana York, Wildlife Art July/August 2007

Star Liana York: Passionate About Art and Life

by Tony Varro

Published online courtesy of Wildlife Art Magazine, July/August 2007

From left to right: Summer Spinning - 15" x 13" x 12.5", Star Liana York, Winter Warmth - 23.5" x 14" x 11", Autumn Harvest - 28" x 20" x 18". Photo by Michael Scott-Blair

When a bad traffic accident forced Star Liana York to take a semester off from college, she lost her financial scholarship. She was determined to finish college, but how was she going to pay for it?

That’s simple for a person with the determination of York. She tended bar. She rented a farm where she trained and boarded horses. And when the owners kicked her out to upgrade the farm, she rented a large house, subletting rooms to other young women and doing most of the cooking for them. Even after she graduated, she kept her ‘mini-dorm’ going to help make ends meet during her first year as a community college teacher. As she says, “You gotta do what you gotta do.”

Star Liana York, Paws a Plenty, Bronze, 20" x 30" x 15"

But there was never any doubt that York would be an artist, and more particularly, a sculptor. At 5 years old, she would go down into her father’s woodworking shop in the basement of the family home and use his jigsaw to cut out wooden figures of animals and people, which she painted. Before graduating from high school, she was molding metal fantasy figures and animals, and selling them in a local jewelry store. She never dreamed she would make a living with her art, but then, she had never been farther west than West Virginia and had never been exposed to the American West, with its variety of wildlife and its peoples—especially the American Indian.

Today, York is widely known and collected, not because of any particular style she has developed, but for the variety of her subject matter and for the emotions and feelings that most of her pieces evoke. “I like to celebrate that special spark of life that the cowboy and cowgirl symbolize. I like the serenity of the Indian people. I like the raw power of nature in the animals, even hen in repose. I like to be passionate about things,” says York.

Star Liana York, Watch Bear, Bronze, 17" x 12" x 13"

Put Yourself on the Line

“Each of us must strike a balance between being challenged and being comfortable. If you’re too comfortable, it’s hard to have passion about anything. You have to care about something; you have to put yourself out there on the line if you are going to have passion about something. I’ve no idea where I get that from. Sometimes I think you either have the ability or you don’t. But I think it is true in all artistic endeavors from music to science, and I include science because I have seen my brother, who is a research scientist, get just as passionate about science as I can about sculpture.”

Star Liana York, Newborn, Bronze, 22" x 36" x 16"

But York draws a clear distinction between art and crafts. “In crafts, you are working with your hands. In art, you may well be involving the hands, but you are working with the mind and the heart. The involvement of those two forces is fundamental to the creation of art.”

York was born in 1952 in a house her grandfather built just outside Washington, D.C., in Maryland, and that is where she was raised. Her mother had been a professional ballerina, and her father was an engineer who built stages for theatrical performances. Her parents met in New York City in the theater world, but moved back to Maryland before York was born, and she was the middle one of five siblings.

Star Liana York, Fat Cat, Bronze, 16" x 21.5" x 10"

“I drew a lot as a youngster and got a lot of praise for my artwork from first grade on,” York recalls. In high school, a teacher had a centrifugal caster and taught its use,

leading York to begin working in metals at an early age. Then she was on to the University of Maryland, the Maryland Institute College of Art and the Corcoran College of Art & Design in Washington, D.C., before becoming a teacher in metal design casting and fabrication at Prince George’s Community College in Maryland.

Gives Up Teaching For Art

“I loved teaching and I loved the students. I think teachers are among today’s most unsung heroes, but I found that teaching drains you for anything else. I wanted to put my creative energy into my own work—I had to try it and see if it would work.” That meant giving up teaching, but it also meant living on the cheap again, and that was something she already knew about. “I rented a four-bedroom house with an attic and a basement converted into bedrooms,” and she was back in the ‘mini-dorm’ business.

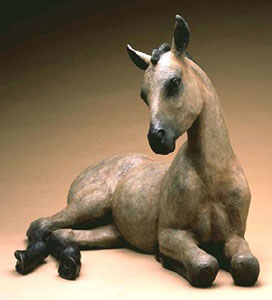

Star Liana York, Baby Jack, Bronze, 7.5" x 6.5" x 3.5"

It was a tremendous gamble, but forces were coming into place that would redirect York’s life. Almost all her work was small—less than six inches high—controlled as much by her style, as by the local foundries, which could not cast anything larger. “When I wanted to do larger stuff, I realized that I needed a new foundry,” says York. “I went to three foundries in New York and another in Baltimore that could handle larger pieces, but it could take a year to get a piece in there. Then, one day, I was in the Smithsonian Institution and saw a display of Remington’s work done by a foundry in Santa Fe, N.M.

Star Liana York, Coyote Family, Back and left to right: Male 18" x 30" x 17", Female 28" x 21" x 17". Front Left to right: Pup 11" x 10.5" x 6.5", Pup 5.5" x 12" x 8"

“About the same time, I met my first husband (Rodney Barker), who was an author. He had lived in Durango, Colo., and wanted to go back West to write, so a road trip out there met both our needs. You can tell where my head was. I was driving up Interstate 25 in New Mexico, looking for the tall buildings of Santa Fe. I’m East Coast—a city means tall buildings, right? I drove way past the city without even seeing it and had to double back. That was 1984. My husband was a Quaker and we were able to stay in a Quaker house on Canyon Road for $5 a night—and there were five foundries in Santa Fe.”

The couple married and moved there in 1985. “And I wanted to get back to riding horses. My sister and I once pooled our babysitting money to share a horse, and I have always loved them. Now I wanted to get out West and ride again, especially in speed events, which are my favorites, and that is really Western riding,” says York, who now lives near Abiquiu, north of Santa Fe.

Star Liana York, Touch the Earth, Bronze, 49" x 24" x 20"

The West Opens New Horizons

Living in the West was a revelation for York. “It was a major cultural experience for me. I could not believe that I grew up in the United States yet didn’t know we had a country within a country, like the Navajo Nation and the Hopi and Zuni peoples.” The Indians had a huge impact on York, who quickly started a series of sculptures depicting Indian women. “I have found the Indian experience intensely moving. They are so in contact with the earth and I love to try to celebrate that culture’s connection to the natural world. Now word this carefully, because I intend it as a sincere compliment: I see the Indian people as being similar to the native animals—they have a self-contentment with who they are and can live peaceably with that and with dignity. There is so much to be learned from these people, people who have stayed in touch with natural things.”

Star Liana York, Cowgirls, Bronze, 17" x 14" x 12"

York’s mind is always open to new ideas with her antennae out, sensing a possible new experience. “We once had a horde of grasshoppers—grasshoppers everywhere. I had an apple tree that was covered with apples but did not have a single leaf. Someone said that turkeys would get rid of them, and they did, but the important thing we learned was that if you let these birds be free to express themselves, each turkey has a different personality—we even had one that we called King George because he was so pompous.

“It’s odd,” she says, shaking her head, seeking to understand her own thinking. “There is an individuality in each animal, yet there is a universality at the same time. It is not just a fox being a fox or a wolf being a wolf; it is being open to something that is more universal in the animal.” That involves something beyond seeing the animal—it involves feeling and passion. “I heard of someone who said they knew all the sculptures they intended to do for the next 20 years. Oh, dear me, I can’t even begin to relate to that. When I get an idea I have to get going on it right now. It feeds the passion, which takes me in the direction of what I am looking for, and as it gets closer, it feeds the passion some more and mounts. I don’t necessarily know what piqued my imagination, but I just know that I have to do it. So I jump in and go for it because out of that comes this kind of obsessive behavior to find out what it is that has drawn me to it in the first place—am I making sense?”

Star Liana York, Cat Call, Monumental Bronze, 21.5" x 67" x 25"

An ardent supporter of programs that help animals and children, York set out to develop a program that led to the now nationally famous New Mexico Trail of the Painted Ponies, which started in late 2000. “I had gathered together a bunch of my horse friends, who loved to dress up in historic Western dress, and invited about 60 artist friends to use them as models. The idea was that the artists could paint and sell whatever they wanted, provided they donated one piece to a program for autistic children.” Then she heard about the fund-raising Cows on Parade project in Chicago, “and I thought, ‘Wow! What a fabulous idea.’ “ It was the first step on the Trail of the Painted Ponies. “I created a model and then a full-sized horse. But it was my first husband who took the idea, did a tremendous amount of work, and built the program into what it is today. I am very proud of what he’s done.”

Life Takes New Direction

First husband became former husband in 2005, when after 20 years of marriage, the couple was moving apart. “My mother had recently died and it turned a light on inside my head, telling me that I needed to decide what I wanted for the rest of my life, and then pursue it. It had been so sad for me to see my parents struggling to be happy together when they were such vastly different people. They achieved a measure of happiness, but I thought my mother deserved a whole lot more than that. Unfortunately, they lived in a time when divorce was not an alternative, even at the cost of happiness.” York is now happily married to fellow artist, Jeff Brock, and the two often collaborate on pieces, especially horses.

Star Liana York, mini bronze horses from Rock Art Mare collection, based on prehistoric drawings

Wildlife, Indians, cowboys—all parade through her studio, but it is the horse that perhaps holds a special place in York’s heart. Her work traces the horse from the prehistoric cave drawings of Europe to the modern equine world. In prehistory, most of the horses drawn in caves were mares, celebrating birth. Over the ages, the horse has come to be more associated as an instrument of war, says York, who still enjoys pieces based on cave art. “I find more freedom in them. I can get away from the more posed nature of today’s horse statues. Their roundness creates the dynamic of expression. I don’t have to focus so much on the eyes, and I can let the motion of the horse speak for the emotion of the horse.

Star Liana York, Grandma's Gifts, Bronze, 24" x 24" x 24"

“For the past couple of decades, I have been involved in training horses, and if you can get close to them, they are incredibly sensitive animals and can be so gentle with, and understanding of, children, especially those with developmental difficulties,” says York. “I’ve always known that dogs can show emotion, but like us, they have carnivore and predator instincts. When we work with a horse, we are working with an animal much bigger and much stronger than we are. Yet, that animal is prey, not predator, and the differences are monumental. The horse is very guarded, but if you can get close enough to the point that the horse will trust you, the horse will open up its personality to you. It will give you a glimpse into a whole new and mysterious world. Getting to understand and know horses has been an eye-opener for me, and has expanded my appreciation of the world in which I live.”

That’s emotion. That’s patience. That’s passion. That’s Star Liana York.

Star Liana York, Mare of the Renaissance, Bronze, 24" x 21.5" x 12"

Tony Varro is a free-lance writer living in Santa Fe, NM.

Images courtesy of Star Liana York, photos by Wendy McEahern unless otherwise noted.