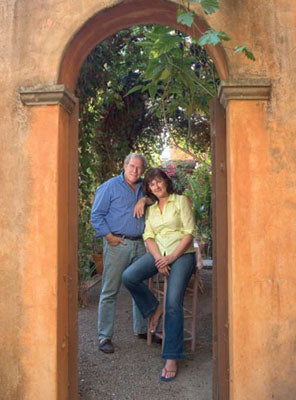

Dennis and Anne Ziemienski, Sonoma Magazine Winter 2007

Spellbound: Entwined in romance, art, worldly adventure, and Gypsy magic, love is a many-splendored Ziemienski.

Story by David Bolling

Photos by Robbi Pengelly

Reprinted courtesy Sonoma Magazine, Winter 2007

Dennis and Anne Ziemienski in their studio

Meet the Ziemienskis. There's a screenplay here. The theme is loss, love and several magnificent obsessions. The romance alone is unreal.

He was a submarine sailor from Vallejo with a passion for painting.

She was a registered nurse from Orinda who lived to belly dance.

He went to New York, designed the Dockers man and illustrated book covers for Elmore Leonard and James Lee Burke.

She went to Cairo and danced her way onto a billboard.

Somehow their paths crossed, and then crossed again.

A mysterious British Gypsy spun magic that finally brought them together.

Now they are notables in the Sonoma Valley art world, with national reputations and the rare distinction of actually living on the income from their creative work.

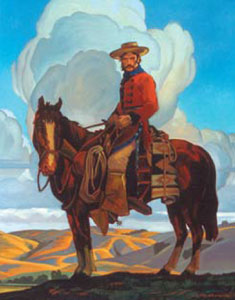

He creates brilliant illustrations and vibrant, representational oils - California and Southwest scenes with deep, rich colors and dramatic vistas. And, oh yes, he designs houses.

She crafts intricate marble mosaics and elaborate pebble patterns for fountains and footpaths. They work together, at home, with Sophia, their artistic daughter - literally a family of art.

Anne’s mosaics are evolving in new directions, like Navajo designs.

Let's start with the romance, since there's enough to qualify for the cover of a bodice-ripper illustrated with a picture of Fabio astride a vaquero horse.

They first met in New York by accident. Dennis was ramping up a career in commercial illustration-working on the Elmore Leonard books, illustrating Armistead Maupin's Tales of the City, and even the cover of Murder at San Simeon, Patricia Hearst's first and (mercifully) only novel.

Anne was visiting a friend named Michelle, who was close to the couple next door - who happened to be Dennis and his future wife, Barbara. They met briefly.

End of scene.

Dennis and a gargoyle fireplace he built in one of the houses he designed.

Flash to Cairo, where Anne was an American belly-dance sensation with her own 12-piece band with bookings "every single day" and her image on a billboard. Michelle was there too, always talking about her good friend Dennis, mimicking his voice, telling "Dennis" stories. Anne began to feel she knew him.

Anne spent two years in Egypt until something inside called her home. In 1987, while working for her brother's Sebastopol clothing company, Anne got a call from Michelle saying Dennis was in Palo Alto and she should get in touch. It wasn't Anne's style. "I never called men," she says.

But for some reason she called Dennis, they did the date and had a great time. Dennis, however, was caught in a cloud of mourning. In the six years since they'd met, he'd married Barbara, who developed breast cancer and died. Then he lost his mother and grandmother. His life was a landscape of subdued grief, not fertile ground for romance, and while they saw each other on and off, something was missing. It was Dennis.

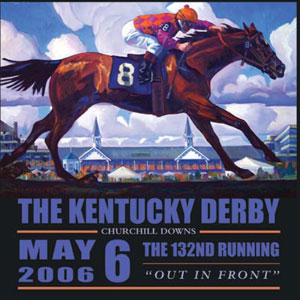

2006 Kentucky Derby, done before the race, magically portrayed a horse with the real winning number. More Gypsy juju?

So later that summer, after several months of inconclusive courting, Anne went off to London to visit a friend. That's when the Gypsy showed up. She barged into Anne's apartment, ranting about a man who needed her at home - the man she would marry - and she presented the incredulous Anne with magic Gypsy juju to sew in the hem of her wedding dress.

"This Gypsy woman, I didn't know who she was," says Anne, "she had me in tears in two minutes. She was pushy, aggressive, she was able to walk in and crack me open in 30 seconds. And that's why we're here today."

When Anne got home it was like someone had thrown a switch. Something had happened to Dennis. "I got back," she remembers, "and the whole relationship had changed."

Anne reclines on Jupiter, mosaic entry art she made for a house designed by Dennis.

Dennis explains: "I resisted for quite a long time. I just can't go from one intense relationship to another. It just didn't seem right." But then the juju, or something, arrived. "I don't know... There was some sort of click in my head."

Fast forward, Valentine's Day, 1989. Dennis and Anne are driving down the coast to the Pelican Inn at Muir Beach, but they're running out of sunlight and they want to walk in the waves. They stop at Stinson Beach and Dennis pulls out a bottle of champagne and a little flipbook he's drawn of a boy and girl rabbit. As the pages flow, the boy rabbit draws a heart and the words, page by page, spell, "Anne, will you marry me?" The heart is empty. Dennis says, "Now it's your turn. This can be either an heirloom or a piece of junk."

Anne fills in the heart with the appropriate one-word response, and voilà, family heirloom.

Villa Ziemienski: Dennis designed it after measuring dimensions of homes all over Italy.

But enough romance, let's talk art.

It may read corny, but it feels profound, is profound, when Dennis says, "Art is like my breath."

He was a kid whose mother gave him crayons, "and I would just draw and draw." By his senior high school year, Dennis knew he had to pursue this passion with the next step-art school. But Vietnam was raging, his father was a nuclear engineer at Mare Island, and so Dennis joined the Navy Reserves, went into submarine service and spent two years largely underwater-spying on Russians, traveling everywhere from Vietnam to Siberia to Pearl Harbor.

One time he went 72 days on a nuclear sub without surfacing. He doubled as the ship's artist (drawing what he saw in the periscope) and mess cook, grew a beard and won a blueberry-pancake-eating contest. In 1970, he got off the ship and out of the Navy, went back to art school on the GI bill and graduated cum laude.

His illustrations have earned national attention - he created the official poster for Super Bowl XXIX as well as last year's Kentucky Derby - but what Dennis loves most is painting. "I'm best at doing something along the lines of traditional painting. When I can put paint down that looks like a face, it's like waving a wand. That's magic."

"The Californio," an iconic Ziemienski image and a typical example of his bold use of color, contrasts with "The Gondolier," a favorite image of Venice.

He was nevertheless mindful of what an instructor told him: "If you want to be successful, it's really hard to paint fine art without a patron." Since even in Sonoma there are no Medici families, putting all your artistic eggs into one fine-arts basket is risky, especially without a day job. That's probably why, along the way from line art to fine art, Dennis began designing houses, including his own.

If the Ziemienski abode looks like a Tuscan import, that's partly because Dennis is half Italian ("The other half is Polish, but I'm Italian from the waist down"), and both Ziemienskis are in love with Italy. After unrolling his tape measure during numerous Italy trips, Dennis created a blueprint for their home, now on a secluded hillside in Glen Ellen's Wolf Run Canyon.

The walls are thick, the ceilings high, the windows tall, the doors taller.

It's a three-bedroom villa, elegant and well lived in, embracing a garden of nearly profligate Mediterranean foliage: a lush grape arbor, riots of roses, hydrangeas, angel's trumpet, Burmese honeysuckle, canna lilies, sago palms, birds of paradise, morning glories, bougainvillea, prickly pear, pomegranate and lemon trees, a vegetable garden. In the courtyard trickles an exact duplicate of a Sicilian fountain, the kind where people washed clothes. Dennis cast all the pieces himself.

A neighbor saw the house and asked, "Who designed it?" When Dennis told him, the neighbor immediately asked, "You want to design mine?" And so he did.

Anne's pebble mosaic footpath winds organically through a lush garden.

He also designed a studio where he and Anne both work in a creative partnership. Ask her to describe Dennis' art and she muses, "Wouldn't it be awful to be married to somebody if you didn't like their art?"

What kind of art would Anne not like? "Cheesy art, like Thomas Kincaid." Dennis is probably safe. "I think his art is very romantic," she says. "He brings a sense of life to his pictures-they aren't empty. It's like they've been alive for a long time."

Anne's trajectory into art was less direct than her husband's. At the nursing school she attended, a friend with scoliosis took up belly dancing to strengthen her back. Anne joined her, got hooked and started a dance troupe that performed for fundraisers. After graduating, she landed a one-year contract as a night nurse in San Francisco but kept belly dancing, falling deeper in love with its mesmerizing music and movements.

When her contract ended, she had job offers from nightclubs in both Hollywood and London. "I asked myself, do I want to be a nurse in San Francisco, or do I want to dance in London? Duh."

She got to London with $200 in her pocket, danced her way to Paris, then Cairo and Alexandria. Anne describes it as fulfilling a quest. "They call Egypt the mother of the Earth. It was so driving, so primitive. To be there in the heart of it was...amazing."

The Egyptians loved Anne, and she loved their music, and for a while, it was magic. "There's nothing as wonderful as Egyptian music. Some people get it, some people don't. Dancing their music I lived it, their humor, their sense of family, the way they are. It's fabulous."

Villa Ziemienski: Dennis designed it after measuring dimensions of homes all over Italy.

But it was also starting to change. Dancing at weddings, she noticed more women fully covered - even their hands masked by gloves. Fundamentalist Islam was spreading, and Anne got out just ahead of the convulsion, before they even "burned some of the nightclubs."

Ensconced in Glen Ellen, Anne still dances and teaches occasional classes, but her Mediterranean impulses flowered in a different direction when she began making marble mosaics. The floor of the entranceway to the Wolf Run villa is inlaid with an eight-food image of Greek goddess Persephone. At the door to the neighbor's house that Dennis designed is Anne's five-foot likeness of Roman god Jupiter.

Anne likes marble because "it feels alive, and the palette's more natural." She cuts the stone herself, with a crimping tool Dennis made (from two-by-fours and a tube from a bicycle tire) that looks more like a medieval torture device. Among her many mosaics are numerous Greek and Roman heads and a portrait of daughter Sophia.

The most exciting moment in her work is when the eyes take shape.

"My favorite thing is faces. A dear friend died and his mother asked me to do a mosaic of him. I decided to do the eyes first, and I'd done about six pieces of marble, literally, and the eyes just jumped alive."

Take one look at Anne's portrait of "Man of Fayum," and the eyes will follow you home.

Anne's mosaics have won more and more admirers, spinning her off from marble into intricate patterns done with pebbles. The stunning 22-foot fountain surround of black and tan pebbles Anne made for a Lovall Valley estate even landed in The New York Times. She describes the labor of assembling thousands of small stones as "a meditation-there's almost nothing in my mind, it's absolute quiet."

The haunting eyes of Anne’s “Man of Fayum” follow you out the door.

Now she's experimenting with Navajo patterns, her restless curiosity pushing her in new directions. "I constantly feel like I'm living four lives at once. I don't want to be frenetic, but there are a lot of directions I feel I could go in."

Ever inspired by her talents, Dennis says Anne is "many artists rolled into one."

If art was all Anne did, she'd still have her hands full. But she's also "very much a mother. It's hard for me to keep my mind on my art. I drive Sophia all over. When I do

have those few days of being alone, the day is gone in what feels like a minute."

Spend a little time with the Ziemienskis and you quickly learn that, as appealing as it sounds to inhabit a world of art, the caveat of making your passion your work is that it's still work - still a job. On one hand, there's nothing Dennis would rather do than "push paint. It's in my system." On the other hand, you live and die by the brush. "This is the only way I know to pay the bills," he says. "I always have to hope it will carry me to the next check."

Anne underlines the cardinal risk of art as enterprise: "I don't think we'd be good business people. As a dancer I didn't market myself. I don't market myself now. A good business person could do so much more."

Thomas Kincaid comes to mind.

That said, the Ziemienskis have wealth you can't measure with money, and it pours out of their home and their work like sunlight. Like romance. Sit with them under the arbor, drink a bottle of red wine with Dennis' art on the label and nibble slices of asiago, surrounded by a profusion of flowers, art scattered everywhere, and you find yourself committing the ultimate social sin - you simply refuse to leave.