Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows, NSS Art of the West September/October 2007

By Medicine Man Gallery on

View available Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows sculpture

Beauty and Grit - Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows

by Sara Gilbert

Reproduced courtesy of Art of the West magazine, September / October 2007

If Deborah Copenhaver- Fellows hasn’t finished up her work in the studio by 5 p.m., she gets a gentle reminder that it’s time to take a break: Her dog rolls over and looks up at her, and the horses come to the window and whinny quietly.

“They all know that it’s five o’clock—it’s feeding time,” Fellows says with a laugh.

Those are happy distractions for Copenhaver-Fellows, a sculptor who shares her studio with husband and fellow artist Fred Fellows. The couple lives on a horse ranch in Sonoita, Arizona, just 30 miles north of the border with Mexico. It’s a beautiful place,she says,with lots of tall oak trees, thick grass, and few people, an ideal place to raise horses, play with puppies, and live a genuine Western lifestyle.

“This is the perfect place for us, ”Fellows says. “We’ve got baby colts and a little burrow named Yum Yum. We’ve got three roping horses and four mares and even one little filly that we sent to the racetrack jus to see what would happen. We are living very happy lives, very full lives.”

Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows, She Flies Without Wind, Bronze edition of 25, 31" x 43.5" x 12". "Tears always rise in my eyes when I see horses perform. They arouse passion in me that fills my imagination and touches my soul. Between a woman and a horse the elements of danger, fear and excitement give rise to the feminine spirit of unbridled independence."

Copenhaver-Fellows’ ranch responsibilities feed directly into her artistic endeavors. Living the life she creates out of clay adds authenticity to her work. The women she sculpts do the things she does; the animals are those that she’s seen and touched a thousand times. “I’m living the life that I’m depicting, "she says. “We both are. Due to the environment that we’ve come to and the life that we lead, there’s a vitality that we’re able to depict in our art. We’re living it, and that shows.”

Copenhaver-Fellows has been living it as long as she can remember. She was raised on a ranch in northern Idaho; her father was a rodeo champion, and her brother ropes as well. She grew up with real life cowboys and cowgirls and remains one herself today.“ When springtime comes, we brand,” she says. “In the fall, we ship. We pull calves to the fire, we castrate. There’s a diminishing number of these real places, these real people, in the West today. My role, and Fred’s role too, is to do some documenting of that.”

Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows, Youth was in the Saddle There, Bronze edition of 35, 30" x 33" x 8". "Badger Clark, a famous cowboy author and poet wrote in one of his poems" Youth was in the saddle there, with half a world to ride" He was referring to the magnificance of youth. The neighbor girl Megan Wilkerson modeled for me in this sculpture. She can rope better than most of the men her young age, she is beautiful (although she doesn't know it), she has confidence and faith. The world is truly hers to ride."

And so, when the horses whinny at the window, Copenhaver-Fellows climbs down from the scaffolding she uses for her larger-than-life sculptures and takes time to feed them. When a puppy curls up in Fred’s cowboy hat, she notices all the nuances so she can sculpt his cozy pose. “That’s the magic, that’s the twinkle,” she says. “That’s what living here has done for us. We’re immersed in our subject matter.”

Copenhaver-Fellows’ subject matter has never strayed far from the horse heads she drew and sold during high school. The way she depicts those horses and the people who ride them, however, changed the moment she first experienced sculpture during a class in college. She liked the feeling of clay in her hands and felt drawn to work in three dimensions. “I loved it immediately and knew that I wanted to do it,”she says. “I knew that I could do it all my life—and that, if I could make a living doing sculpture, I’d never work a day in my life.”

Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows

Copenhaver-Fellows graduated from Fort Wright College in Spokane, Washington, in 1970, having already received a commission for a piece for the mayor of that city during her senior year. Commissions and monuments were the base of her career in the early years; her first was a monument of Bing Crosby for Gonzaga University. During a 10-year period, she created several larger-than-life-size monuments, including the Inland Pacific Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial and the Korean War Memorial for the State of Washington, as well as several other commissions.

Working on such large pieces took enormous amounts of time—one monument could consume between nine months and a year of her life. Although Copenhaver-Fellows had developed relationships with a few galleries after college, she soon realized that she had little time to complete smaller-scale sculptures to sell. “At one point, I realized that I had to pull my work back from the galleries, ”she says. “I couldn’t continue to send new, fresh salable materials, which is what the galleries want, because I was working on so many monuments. I just told them that I was really immersed in the commission side of art and had to pull out, but that I would be back.”

It wasn’t until she married Fellows in 1990 that Copenhaver-Fellows had the time to do that. She had been raising her daughter, Fabienne, on her own since her marriage had ended in divorce several years earlier, while also working to establish a name for herself as a sculptor. Although she had met Fellows professionally years earlier—he had even written a letter recommending her for her first monument—it wasn’t until after his first wife died of cancer that the two developed a more personal relationship. He was 56 and his children—four girls and a boy—were grown up and gone, but he was happy to welcome Deborah and Fabienne, then 6, into his life.

Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows, Branded . . He's Mine Forever, Bronze edition of 50, 29" x 14" x 7". "In the West, ranchers know which cattle are their's by the brand that they put on them. The brand is held in pride. A pretty girl has her own kind of brand . . . love, and it lasts forever."

Fellows already was a well-known painter and sculptor; his new wife had earned a similar reputation for her monuments and sculptures of pioneer women. Copenhaver-Fellows backed away from the large, time-consuming commissions and focused more o npieces of her own choosing, which allowed her to segue back into the gallery scene. Then, in 1999, the couple moved from their home on Flathead Lake in Big Fork, Montana to Arizona. "Fred has always been one to look for a place where there's no people," she says. "We were as close to Canada when we lived in Montana as we are now to Mexico."

That move and the change of scenery it brought with it had an incredible impact on both artists. "There's so much glorious subject matter here," Copenhaver-Fellows says. "Every day brings a different idea. I'm just so excited about life here, about depicting what I see."

Women have always factored into Copenhaver-Fellows' work. In the early years, she focused on pioneer women because no one else seemed to be depicting them. "There really had been no focus on femininity in the western art scene until then," she says. "No one else was really showing the role that pioneer women played in breaking down the West."

The subject was interesting to her as a woman of the West, and the fact that the market was wide open made it an even better choice. But Copenhaver-Fellows says that she would have chosen the same subject even if that weren't the case. "It is important to find an area that you can fill, something that isn’t being done by someone else,” she says. “But more than that, you need to follow your heart. To find an area that fits both, that’s when you’re really blessed. There aren’t many openings like that these days.”

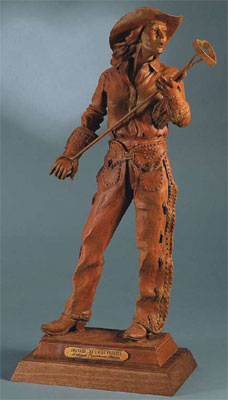

Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows, Everett Bowman Watching the Barrier, Bronze, 10.5" high. As a result of Everett Bowman's efforts the first organization for professional rodeo was started in 1936, the CTA. The "Turtles" with Everett as their leader dignified professional rodeo. Here Everett watched the barrier, the cattle and the cowboys he is competeing against with his jovial competitive character.

Now Copenhaver-Fellows finds herself sculpting more contemporary women—the cowgirls she sees working in real life every day. Her pieces show both the beauty and the grit of real women working the West today. And, even though she’s not the only artist doing such subjects, she’s still finding a market for her work. “I think I hit on something that’s very good for me,” she says. “Sure there Western female art, but that’s okay. It fits me so well.”

So does sculpture itself. Copenhaver-Fellows still loves every part of the process, from photographing her subjects to manipulating the clay in its final form, even though the physical demands of her medium seem to catch up with her as the years go by. “Sculpture is a lot of physical work,” she says.“When you’re putting on a couple hundred pounds of clay and climbing up and down scaffolding, that’s physically demanding. I have to be careful with my hands and my back now, because I’ve still got a lot of years of sculpting ahead of me.”

Deborah Copenhaver-Fellows, Giving Thanks, Bronze, 50" high. A quiet moment as a rancher gives thanks for the blessings of rain, grass and a way of life.

Even after all the years she has behind her, Copenhaver-Fellows finds herself amazed at the work she’s able to do. She remembers a time years ago when she finished a piece and left her studio very late at night. For some reason, she opened the door again and flicked on the light.

“When I looked in, I saw that piece not with my eyes but with someone else’s,” she says. “And when I did, it was like I had just been a conduit to something that was being said there. Maybe that sounds arrogant, but it isn’t. It’s actually very humbling. The only time you’re truly humbled is when you achieve a level of excellence and you realize that you can’t really take credit for it at all. You’re just a conduit."