C.M. Russell, Masterworks

By Medicine Man Gallery on

C.M. Russell, Masterworks

The Masterworks of Charles M. Russell

Charles Marion Russell, In Without Knocking, 1909, Oil on Canvas, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX

First-ever retrospective of renowned Western artist Charles M. Russell features more than 60 works in oil and bronze.

By Joan Carpenter Troccoli, Senior Scholar at the Denver Art Museum's Petrie Institute of Western American Art

Published online courtesy Western Art Collector, October 2009

Charles M. Russell's paintings and bronzes are familiar to millions and prized by collectors. Russell's art continues to influence American Western painters and sculptors, and his distinctive way with words has affected entertainers and political commentators from Will Rogers on. Despite his fame and influence, however, Russell has not been the subject of a major retrospective exhibition until now. In recent years, outstanding curators and scholars have produced exhibitions, books, and essays focused on various aspects of Russell's work, and a fine biography is in print. The catalogue raisonne of Russel's paintings and watercolors was published in October 2007.

The Masterworks of Charles M. Russell: A Retrospective of Paintings and Sculpture is co-organized by the Denver Art Museum's Petrie Institute of Western American Art and the Gilcrease Museum, and consists of 60 major works in oil and bronze, plus includes 15 supplementary works devoted to the charismatic artist's presentation of his own life story and his artistic, personal, and political outlook. The principal part of the exhibition is divided into six sections that proceed from Russell's depictions of contemporary cowboys to his increasing engagement with subjects that evoke a lost Western past.

Charles Marion Russell, The Camp Cook's Troubles, 1912, Oil on Canvas, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK, 0137.913

For those accustomed to filing Russell away as the original "cowboy artist" and no more, this exhibition will hold many surprises, beginning with the variety of his subject matter and the range of his expression. Russell's detailed depictions of minute details of cowboy gear and complex movement under a blazing Western sun have never been surpassed, but he also made many works that are retrospective in subject, carefully studied in form and color, and elegiac in mood. The depth of Russell's genuine concern about the destruction of the native peoples and landscapes of the Northern Plains, as well as his tolerance of human difference in general, was extraordinary for his time. Russell viewed Indians as dignified, complex human beings who held the only truly authentic claim to the West, and he protested the official injustice and public indifference that attended their removal from ancestral lands. He made women - especially Indian women - the subject of a substantial number of his works. The revelation of this exhibition may be that Russell's work was less a celebration of cowboys than of Indians; in fact, his depictions of Native Americans outnumber those of cowboys by three to one.

Charles Marion Russell, Self Portrait, 1900, Watercolor on Paper, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, WY

In addition to revising conventional conceptions of Russell's subject matter, the exhibition and its accompanying publication are designed to encourage a detailed examination of the esthetic components and stylistic development of his work. Russell's formal training was virtually non-existent, but, thanks to self-discipline, tremendous powers of observation, and a dogged commitment to solving challenging compositional problems, he achieved remarkable technical mastery. In essence, Russell educated himself and he went about it with considerable energy and desire, drawing formal and iconographic inspiration from sources high and low, including illustrations in books and mass market periodicals, popular prints, and the works of earlier American Western artists such as George Catlin, Karl Bodmer and Carl Wimar, as well as his contemporary Frederic Remington. Russell's visits to the displays of fine art at the World's Fairs in Chicago in 1893 and St. Louis in 1904 were seminal events in his professionalization, as were his trips to New York, which began in 1904. Thereafter Russell increasingly participated in the larger art world and the resulting improvement in his work was dramatic. He painted with academically trained artists in their New York studios, and the New Yorkers also came to him, visiting his "log cabin" studio in Great Falls and his summer home in Glacier National Park. He explored big-city galleries and museums, not just in the United States, but also, on the occasion of a one-man exhibition in London in 1914, briefly in Europe as well. Charlie Russell even toured the 1913 Armory Show in New York.

Charles Marion Russell, Buffalo Hunt (No. 39), 1919, Oil on Canvas, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX, 1961.146

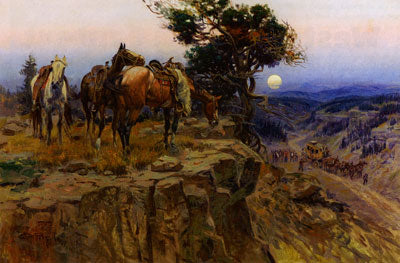

The exhibition opens with the action-packed cowboy paintings for which Russell is best known; and concludes with his heroic portrayals of wildlife in pristine Western settings undisturbed by the white man. Russell did not proceed in lock step from one neatly delineated formal and thematic period to the next, but a survey of his career present, along with increasing proficiency, a retreat from a dynamic present containing the seeds of a mechanized future to a sunset-gilded primeval paradise of wild creatures and landscapes. The sections into which the exhibition is divided correspond to this trend in Russell's art, and his increasing alienation from modern urban civilization and growing devotion to the natural is the exhibition's principal unifying concept.

In Russell's work, "the natural" does not equate to wilderness, although wilderness is an aspect of it. Russell's sense of the natural encompasses much more, including an empathetic, often humorous, understanding of fundamental human needs and drives, a quest for humanity. Russell's idyllic natural realm exists in opposition to modern urban civilization, which is the domain of the artificial, the mechanical, the hypocritical, the constrained, and every other product of the impersonal march of progress. Russell vigorously dissented on Prohibition, winked at prostitution, and, at times, sympathized with outlaws, not to mention the animals that fall prey to the sportsman. The native peoples of the Northern Plains were Russell's ideal, their human failings all but cancelled out by their tragic fate. Russell wrote of them (characteristically eschewing punctuation), "their God was the sun their church all out doors their only book was nature and they knew all its pages."

Charles Marion Russell, Indian Maid at Stockade, 1892, Oil on Canvas, JP Morgan Chase Art Collection

In centering his art on the natural, Russell carried forward into the 20th century earlier Americans deep-seated misgivings about the consequences of industrial progress. His anxiety was hardly unique in his day. However, Russell's work is distinguished by a degree of personal investment rarely encountered in the art of his predecessors or contemporaries. His rejection of modern technology and the city, coupled with his celebration of Indians as the first and only "real" Americans, was not uncommon in the United States around the turn of the 19th century, but his genuine knowledge of and sympathy for those displaced by progress was not.

Charles Marion Russell, The Medicine Man, 1908, Oil on Canvas, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX

The exhibition's other major theme is the striking degree to which Russell plated the role of cultural intermediary in his work. He did so for the cowboys who, for all their elevation as heroes in popular culture, were disdained in life by polite society, or, with greater seriousness and sometimes to the point of public protest, for Indians. His comments on the divide between white Americans professed ideals and the reality of their behavior were sometimes sweetened with humor, but never lacked an acidic edge.

Charles Russell was the indulged son of a well-to-do businessman with deep roots in St. Louis, the launch pad for Western enterprises from Lewis and Clark on, as well as a gathering point for Indians from the far West. Russell's family was well up in St. Louis society, but he tended to identify with those of his relatives, such as his maternal great-uncles William and Charles Bent, famous traders on the Santa Fe Trail, who abandoned urban civilization in favor of life beyond the frontier. William Bent took a Cheyenne wife; his brother, who lived in Taos, married a Mexican woman. Two of William's sons lived as Cheyenne warriors; one of them, named Charles like his cousin in St. Louis, became notorious for terrorizing frontier whites.

Charles Marion Russell, When Shadows Hint Death, 1915, Oil on Canvas, The Duquesne Club, Pittsburgh, PA

Russell was something of a prodigal himself, having left home to live on his own in Montana Territory at age 16, his parents having finally acceded to his childhood desire to live in the far West. Not long after his arrival, Russell began to sport around his waist a colorful woven sash identified with the métis, an oppressed Canadian group of French and Cree Indian heritage. In addition to the sash, which became a lifelong sartorial trademark, Russell enjoyed dressing up in Northern Plains clothing from his large collection of native artifacts, took pleasure in his physical resemblance to Indians, and portrayed himself as an Indian in some of his illustrated letters. He delighted in his "Indian" name, Ah-wah-cous (Antelope), even though it amounted to a joke on himself, and he never bothered to correct the myth that he spent the winter of 1888-89 living with the Blood tribe of Blackfeet north of the Montana border in Alberta, Canada. Despite his fancy pedigree and his own eventual wealth and lionization, Russell consistently sided with marginalized people.

In Russell's art, the character of the encounter between whites and others in the West is remarkably varied. It can be hostile, wary, curious, comic, baffled, accommodating, cooperative, violent, or tragic, but it is rarely simplistic. As a westerner and proud descendant of a family that had enjoyed a full range of frontier experiences, Russell was in a better position to offer a sensitive - and often more historically accurate - reading of the myriad exchanges between cultures that took place in the West than artists based in the East, as the vast majority of 19th-century American Western artists were.

Charles Marion Russell, Innocent Allies, 1913, Oil on Canvas, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK

In his iconography, Russell emulated the mingling of white and Indian that some of his forebears achieved in life. Throughout his work, Russell demonstrated an extraordinary interest in communication in every form and across every sort of human and even animal barrier. On an artistic level, Russell connects by means of his choice of subject, materials, and technique, as well as the structure, point of view, and atmospheric and narrative elements of his works, which often bear and illuminating ironic, or humorous title. Russell amplified and modulated the import of his own compositions by quoting from the works of other artists. He found writing difficult, but he was a great reader and a connoisseur of colorful, precise language. Given the literary (as opposed to merely anecdotal) qualities of many of his works, one can't help thinking that his reading of such romantic authors as James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, Sir Walter Scott and Francis Parkman, as well as the less exalted texts of dime novelists and regional specialists, was as crucial to his art as the images he harvested from books and magazines.

Russell's work presents a veritable catalogue of the ways in which the gap between cultures, genders, species, and even historical epochs can be bridged, and one always senses that he wanted to make that crossing himself. Russell enriched his work with the meaningful, formally effective use of sign language, pictographs, petroglyphs, smoke signals, shadows, war paint, cattle brands, and human and animal tracks and scents, as well as the appearance in the landscape of specific topographical features and such unnatural phenomena as wagon roads, railroad tracks, longhorn cattle, and steamboats. As Russell's adoption of the métis sash suggests, he considered clothing, as well as his own personal image, to be means of communication that relay both difference and an underlying solidarity.

Charles Marion Russell, Meat's Not Meat Till It's in the Pan, 1915, Oil on Canvas Mounted on Masonite, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK

In building an iconography of every imaginable Western sign and its interpretation (or misinterpretation) by figures within the work as well as the viewer, Russell set up a system of insiders and outsiders. Some know the code; many don't. Although he controlled this realm, Russell's own place within it was ambiguous, bringing to mind the role of Owen Wister - or, rather, the first-person narrator - in The Virginian. Even though The Virginian's origins are far lower on the social scale than his own, the narrator wants, above all, to be worthy by dint of knowledge, character, and accomplishment, of the friendship of his self-made cowboy hero. One can't help feeling that Russell, who was invited by Wister to illustrate The Virginian and had more than a little in common with its title character, attempted something analogous with his art. Russell's work is nostalgic, but, as we hope to demonstrate in this exhibition, it is aspirational, too. From art, literature, and popular culture, Russell made a world that would forever resonate in the American imagination, and then endeavored, by virtue of his artistic skill, to earn a place within it.