Maynard Dixon's Vision of Nevada

By Chadd Scott on

Ask me what I like most about Maynard Dixon and without hesitation I’ll tell you his Western landscapes. Yet for the second time writing about a Dixon exhibition for “Essential West,” it is a figurative painting of his that most captivates me.

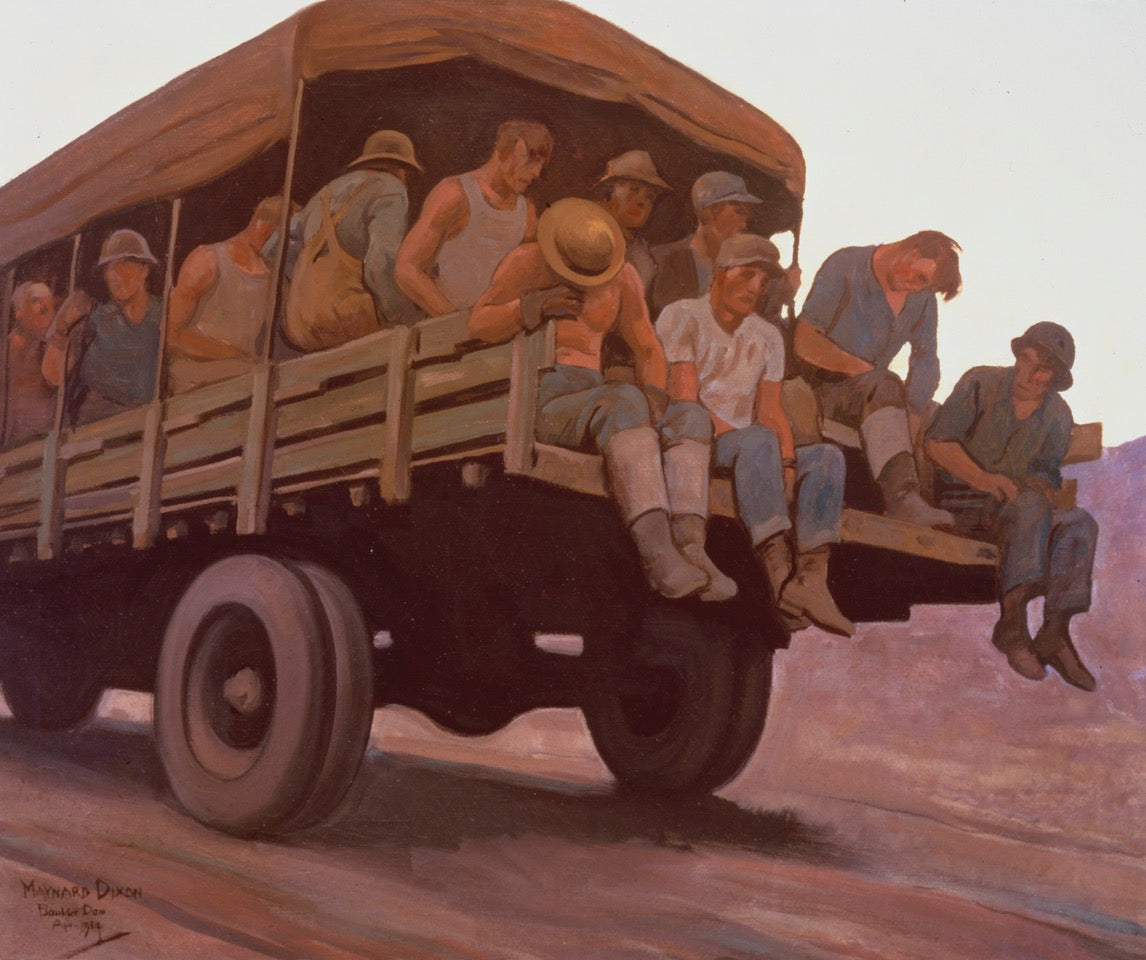

Tired Men from 1934 was produced as part of a commission Dixon (1875 – 1946) received from the federal Public Works of Art Project, a government program offering artists jobs to help keep them afloat during the Great Depression. Dixon’s job was documenting construction of the Boulder Dam, now known as the Hoover Dam, not far from Las Vegas.

Depicted are slumped workers riding in the back of a flatbed truck – tired men – presumably returning from a hard day’s labor working earth, concrete and steel under the punishing Nevada sun. Dixon’s empathy for working people reveals itself.

He, too, felt the bite of the Depression. The despair. The pressure of providing for a family. He, too, knew the bone weariness of working long hours outdoors. He knew what it felt like to be riding in the back of that truck – all of it.

Art Historian John Ott has written of how Dixon’s Boulder Dam paintings “...depart dramatically from the nostalgic frontier scenes with which he established his reputation. These two dozen artworks are a critical watershed of his oeuvre...mark[ing] a stylistic departure that would continue to evolve.”

Of note, Dixon’s marriage to famed photographer Dorothea Lange was crumbling at this same time. It’s easy imagining his emotions being raw. A personal depression settling over him to coincide with the global Great Depression.

“Dixon’s life and art are a record of his relentless search for solitude and personal healing in the high desert of Nevada,” Ann M. Wolfe, Andrea and John C. Deane Family Chief Curator and Associate Director at the Nevada Museum of Art, said. “Dixon’s 1935 paintings made around the time of his divorce … have titles like Lonesome Hills of Nevada or depict lonely and desolate desert landscapes that suggest he was undergoing a period of loss and loneliness at this time.”

If a man were ever going to produce a brilliant bummer of a painting, it was Maynard Dixon in 1934, marriage failing, depression, and the Depression, seeing men break their backs taming the Colorado River, damming nature, ruining the wild and scenic Southwest he so dearly loved in the name of “progress.”

Historian Kevin Starr has noted that a driving impulse for Dixon was “a sense of imminent loss” of the geography, history, folklore, and culture of the American Frontier on the Old West.

Tired Men and Dixon’s Boulder Dam paintings are one highlight of a stunning highlights filled presentation of his work on view during “Sagebrush and Solitude: Maynard Dixon in Nevada” at the Nevada Museum of Art through July 28, 2024.

Maynard Dixon in Nevada

Dixon traveled widely in Nevada over the first four decades of the 20th century, producing hundreds of paintings, drawings, and sketches of his observations, some on site, others in his California studio. His sojourns there read like epics from long distant adventure novels, nearly unimaginable to the 21st century mind.

Like in 1901 how he and his artist-friend Edward Borein traveled from Oakland to Carson City on horseback for the first leg of a thousand-mile-trek through the Northern Great Basin. Throughout, both sketched and studied cowboy life and the ranches they visited.

Among Dixon’s favorite places to paint were the northernmost regions of Nevada, not far from the Oregon border where he depicted multiple views of Thousand Creek Gorge, Virgin Valley, and Alder Creek Ranch.

A partial accounting of his time in the state also includes a visit during the late summer of 1927 when he set out for northwest Nevada initially planning on a two-week excursion, ultimately staying four months.

He and Lange summered at Anita Baldwin’s 2,000-acre estate at Fallen Leaf Lake, CA just across the state line in 1932. Baldwin was the daughter of E. J. “Lucky” Baldwin who made his fortune on the Comstock Lode in the 1870s. She was a longtime friend and patron.

Then there was the Boulder Dam commission in 1934.

His time in Nevada extended beyond his marriage to Lange.

Dixon filed for divorce in 1935 in Carson City.

Two years later, Dixon and Edith Hamlin, a San Francisco painter and muralist, packed their painting equipment and returned to Carson City where they were married, staying for several weeks to work.

Dixon adored Carson City, painting the changing colors of poplar and cottonwood trees throughout the year, venturing further afield to Lake Lahontan, Pyramid Lake, and to Lone Pine, CA, a small town not far from the Alabama Hills and Mount Whitney just across the border. There, in 1929, he produced an exceedingly rare series of formal portraits of the people he encountered – Mexicans, Natives, his artist friends and hosts William “Bill” Skinner and Charlotte Skinner.

Six of these portraits appear as part of the exhibition’s nearly 150 Dixon paintings of Nevada and the Eastern Sierra, many of them rarely or ever seen before.

In 1939, as Dixon’s life-long asthma evolved into emphysema, he and Hamlin sought a permanent residence in a more tolerant climate. Carson City was their first choice – they spent weeks there thinking about moving – however, Dixon decided the cold winters would exacerbate his condition and opted for the warmer climate of the Sonoran Desert around Tucson.

He never returned to Nevada.

Maynard Dixon: Modernist

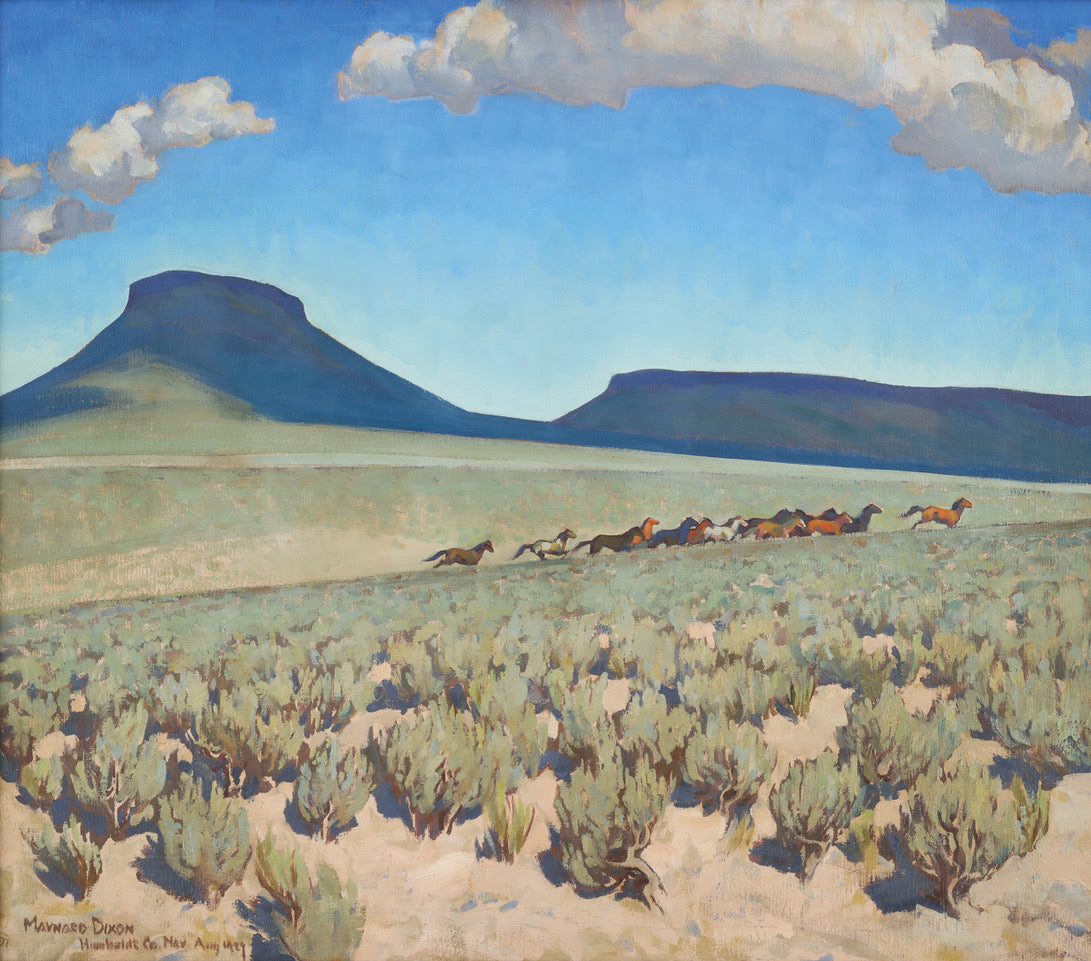

Dixon’s engagement with Modernist painting techniques emerges in the exhibition along with his empathy and deep reverence for the state. Wild Horses of Nevada (1927), a 44 x 50-inch Art Deco inspired painting with a graphic, mid-century travel poster feel to it stands as a prime example. It’s angular, geometric, and depicted from an unusual, overhead perspective.

“Dixon painted Wild Horses of Nevada in his San Francisco studio following a four-month visit to northwestern Nevada in 1927,” Wolfe, who curated “Sagebrush and Solitude,” said. “The bird’s-eye view shows a band of wild horses galloping across a stark, desert alkali flat. Dixon’s choice to emphasize the geometry of the distant mountains, incorporate dramatic shadows, and eliminate all unnecessary details are evidence of his increasing embrace of modernism.”

Thanks to his immersion in the San Francisco art world of the early twentieth century, Dixon was exposed to national and international trends and artistic styles, such as Cubism. These movements, broadly, emphasized the underlying geometric shapes of subjects.

Unlike earlier landscape painters in Nevada – or, in fact, all Western painters who came before him – Dixon began emphasizing shape and form over literal reproduction. C.M. Russell and Fredric Remington are considered the patriarchs of Western art, but while taking nothing away from their work, compared with where Dixon was moving the genre in the years following their deaths, Russell and Remington, artistically, feel old-timey.

By eliminating unnecessary details, employing a limited color palette, and focusing on geometric structure, Dixon became the father of modern Western art, a tradition that would be further expanded upon by Fritz Scholder, Ed Mell and countless painters working today.

Dixon’s occasionally radical modern portrayals of the Western landscape contradict his avowed desire for the “Old West” as he imagined it. Dixon, like Russell and Remington, longed for the West as it used to be, whatever they considered that to be. While all three were looking for and at the West through the rearview mirror, only Dixon painted it through the windshield.

His artmaking’s interest in social justice – one can’t help crediting Lange in part for this – as well as its engagement with Modernism – again, presumably influenced to some degree by Lange who chose the relatively new tool of photography as her chosen medium – both apparent in “Sagebrush and Solitude,” make Dixon continually feel brand new to look at, even a century later.

Medicine Man Gallery founder and owner, and Dixon author and collector, Mark Sublette will be giving a lecture on July 26th at the museum on “Maynard Dixon’s American West.” Medicine Man Gallery is adjacent to the Maynard Dixon Museum in Tucson.

A gorgeous coffee table book capturing Dixon’s time in Nevada and reproducing the artworks on view in the exhibition is available for purchase online and at Medicine Man Gallery.