Meet the Matriarchs of Oklahoma Native Art

By Chadd Scott on

Oklahoma ranked last among all states and the District of Columbia in a study of best places to live for women published by Wallethub.com on February 26, 2024. The publication researched 25 key quality of living indicators including financial, social and health outcomes.

Rest assured, most of those outcomes for Native women in Oklahoma would be even worse, mirroring national data consistently showing Native women experience greater hardship across a broad spectrum of lifestyle markers than other women.

Keep this in mind should you visit the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City’s new exhibition highlighting seven living Native women artists.

Gourd Jar, by Jane Osti, Cherokee, ceramic. Mary Ann and Ken Fergeson.

“It’s a brutal state to be a woman in,” exhibition curator and Oklahoman America Meredith (Cherokee) said.

Mary Adair (b. 1936; Cherokee Nation), Sharron Ahtone Harjo (b. 1945; Kiowa), Adeline “Allie” Chaddlesone (b. 1948; Kootenai), Ruthe Blalock Jones (b. 1939; Shawnee/Delaware/Peoria), Brenda Kennedy (b. 1946; Citizen Potawatomi), Jane Osti (b. 1945; Cherokee Nation), and Virginia Stroud (b. 1951; Keetoowah Cherokee/Muscogee) beat the odds, became successful artists, and are featured in “Lighting Pathways: Matriarchs of Oklahoma Native Art.” The show centers artwork from the 1970s and 80s when these women were establishing their careers.

“Galleries would give them a lower commission than the men,” Meredith, who’s an artist herself and publishing editor of First Americans Art Magazine, explained of one of many slights Native female artists experienced during the era. “Sharon Ahtone often had to sign her paintings ‘Ahtone Harjo.’”

Male artists being paid more for their work – males across the country in all sectors being paid more for the same work – and female artists signing their art to disguise their gender are, sadly, not phenomenon unique to Oklahoma or Native women.

While recognizing the obstacles, “Lighting Pathways’” primary objective is celebrating these groundbreaking women and the time they rose to prominence in. The 1970s and early 1980s witnessed an exuberant, near mania, for Native American art and fashion nationwide including Oklahoma.

Jim Morrison wearing a concho belt on stage fronting The Doors. Sonny and Cher on national TV wearing squash blossom necklaces. Turquoise and silver everywhere.

“Allie Chaddlesone provided this great photo of Willie Nelson with one of her pieces because he went to Anadarko Indian Expo and bought one of her paper castings,” Meredith said. “There was widespread interest, and since these are Oklahoma artists, Texas was really important too. A lot of country musicians, not just Willie, collected Native art – and actors.”

Booms bust, however, and though these artists and the ardent supporters of Native American art remained steadfast, mainstream interest dried up during the mid-80s, coinciding with a decline in oil prices.

“Younger people might not (understand) how important Oklahoma was as an art scene pretty much from the 30s until the oil bust,” Meredith said. “It’s still going in the 80s, but the oil bust was big. A lot of local wealth dried up and a lot of people dumped their art collections onto the secondary market which deflated prices.”

'Lighting Pathways' exhibition installation. Photo by Eric Singleton at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

Connections

As Native women from Oklahoma of mostly the same generation, working in the same profession, the “Lighting Pathways” artists shared numerous connections. They were a community.

Some were related. They’d see each other at galleries and shows. Primary among those was the Philbrook Indian Annual in Tulsa.

“Post War, people don't realize how small Santa Fe Indian Market was and how incredibly important the Philbrook Indian annual was,” Meredith explained of the event held from 1946-1979.

Many of “Lighting Pathways” artists also had work in the 1985 national traveling exhibition “Daughters of the Earth.”

“Bacone College is another major important hallmark,” Meredith adds.

Bacone is a private tribal college in Muscogee, OK. The School of Indian Art there has been producing leading artists since its founding in 1935, including several of the “Lighting Pathways” artists.

Meredith credits longtime former Bacone art school director Dick West (b. 1912; Cheyenne-Arapaho) as an especially important figure.

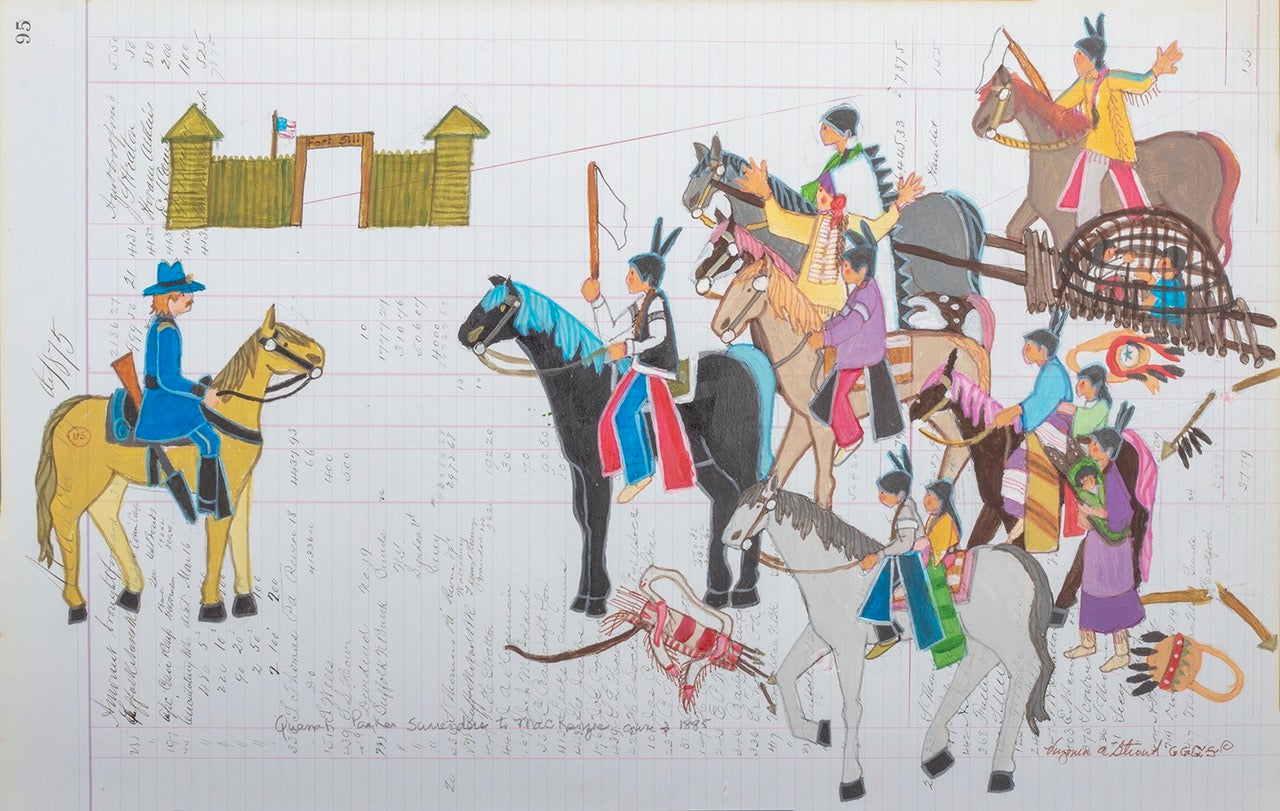

“He really encouraged both Sharon (Ahtone Harjo) and Virginia (Stroud) to pursue ledger art,” she said. “That's a history that is completely lost on current people; they don't understand that these women, encouraged by their community – Sharon knew about ledger art because her family members were ledger artists – people don't understand that they were instrumental in the revival – with the blessing of their tribes and leaders – so Dick West was incredible for encouraging many women artists.”

Native Art for Native People

Santa Fe, generally, is regarded as the epicenter of Native American art. That’s understandable. That distinction, however, results as much from the market as the makers.

“Oklahoma compared to Santa Fe, for the most part, isn't a tourist destination – not to the level of Santa Fe – and we always compare each other,” Meredith said.

Northern New Mexico, Santa Fe, and Taos have been tourist destinations, especially for the arts, since before statehood in 1912. Native people there have been producing artworks in part as souvenirs for tourists since the first trains arrived.

Oklahoma had no such market of outsiders visiting in big numbers wanting to purchase art.

“In the 20th century, and especially at Bacone, a lot of the works were created with Native people as the intended audience, and a lot of the artwork was to convey information to tribal members,” Meredith explained. “That art was a way to transmit information about regalia and dances and ceremonies and beliefs and history – a lot of history – to our own people.”

Necessary information when considering the time period the “Lighting Pathways” artists grew up in.

“The 1950s was relocation time, termination time, it was a dark time for Native people,” Meredith said. “To have this intergenerational passing of information is invaluable.”

Information wasn’t the only thing these artists passed along.

“I think all the artists would feel quite satisfied that many of their younger relatives have gone on to be artists – children and grandchildren – or work in the arts,” Meredith added. “And they've been able to see the tribes have this wonderful resurgence.”

As for the Native arts scene in Oklahoma today, Meredith likes what she sees.

“It's very complex and varied. There's a lot of things happening, a lot of motion – not in one direction – which is great because there's 38 federally recognized tribes in the state,” she said. “I think the potential is incredible and I think artists get to choose a lot of different directions; through the work of previous people, doors have been opened up for us.”

“Lighting Pathways: Matriarchs of Oklahoma Native Art” can be seen at the Cowboy Museum through April 28, 2024.