Gorman Museum of Native American Art celebrating 50th anniversary and new building

By Medicine Man Gallery on

Visitors to the new Gorman Museum of Native American Art on the campus of the University of California, Davis are greeted by a large, circular artwork at the entrance based upon Native American basketry designs. The piece was created by Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie (Seminole, Muscogee, Diné), who in addition to being an artist, is the museum’s director and a professor in UC Davis’ Department of Native American Studies.

Gorman Museum of Native American Art at UC Davis exterior. Courtesy of the museum

The pavilion honors the late Bertha Wright Mitchell (1936-2018), a Patwin basket weaver who in the late 1990s was the only documented fluent speaker of the Patwin language. One of one.

The United States government learned early on and practiced with vigor that if you want to eliminate a people, a good way to do so is by eliminating their language. Assimilation. Boarding schools. Cultural genocide.

Mitchell was a survivor, however, and late in her life helped lead tribal efforts to resuscitate the Patwin language which carry on today.

UC Davis is located on land that has for thousands of years been home to the Patwin people. Presently, there are three federally recognized Patwin tribes: Cachil DeHe Band of Wintun Indians of the Colusa Indian Community, Kletsel Dehe Wintun Nation and Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation.

Bigger and Better

The all-new Gorman Museum of Native American Art reopened to the public on September 22, 2023. It occupies the university’s former Faculty Club. The 1970s building was entirely renovated to house the museum, a process which took more than two years and achieved LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Gold-level standards along the way.

Previously, the Gorman’s collections and programs were spread across multiple buildings on campus with just 1,200-square-feet of exhibition space. The new museum has 4,000-square-feet of exhibition space. Along with room for temporary exhibitions, it features a gallery displaying works from the collection on a rotational basis and visible storage to give visitors access to the collection.

All under one roof. It’s a tight squeeze, but a vast improvement.

Visitor accessibility, care of the collection, climate control, security and lighting have all been vastly improved allowing the Gorman to meet industry accreditation standards. For the first time, the Gorman has a gift shop which has become a big hit with visitors. For sale are small items sourced directly from Native artists and artist cooperatives across North America including Eighth Generation from Seattle and the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

The building’s location along Old Davis Road adjacent to the arboretum makes finding the museum much easier. In a wonderful bit of serendipity, the arboretum’s California Indigenous Garden is nearly on the museum’s doorstep.

The building, a single-story structure with deep eaves common in California architecture, is painted with bands of green representing tule grass, a once-common plant in California used by Native American people to make baskets, clothing, tents, houses and boats.

The museum is named in honor of the late artist Carl Nelson Gorman (Navajo; 1907 – 1998), a founding faculty member in the UC Davis Department of Native American Studies. He was also a World War II Navajo code talker.

The department, founded in 1969, is one of the oldest Native American studies programs. UC Davis is one of just three U.S. universities offering a doctorate in Native American studies.

The museum is an integral part of the UC Davis Gateway cultural corridor connecting UC Davis cultural gems: the Robert and Margrit Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts and the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art. The Gorman Museum also physically links the Gateway with the departments of Art and Art History, Music, Theatre and Dance and the UC Davis Arboretum and Public Garden.

The museum is easily accessible from Interstate 80. There’s a parking lot right next door with free parking on weekends, making that a particularly good time to visit.

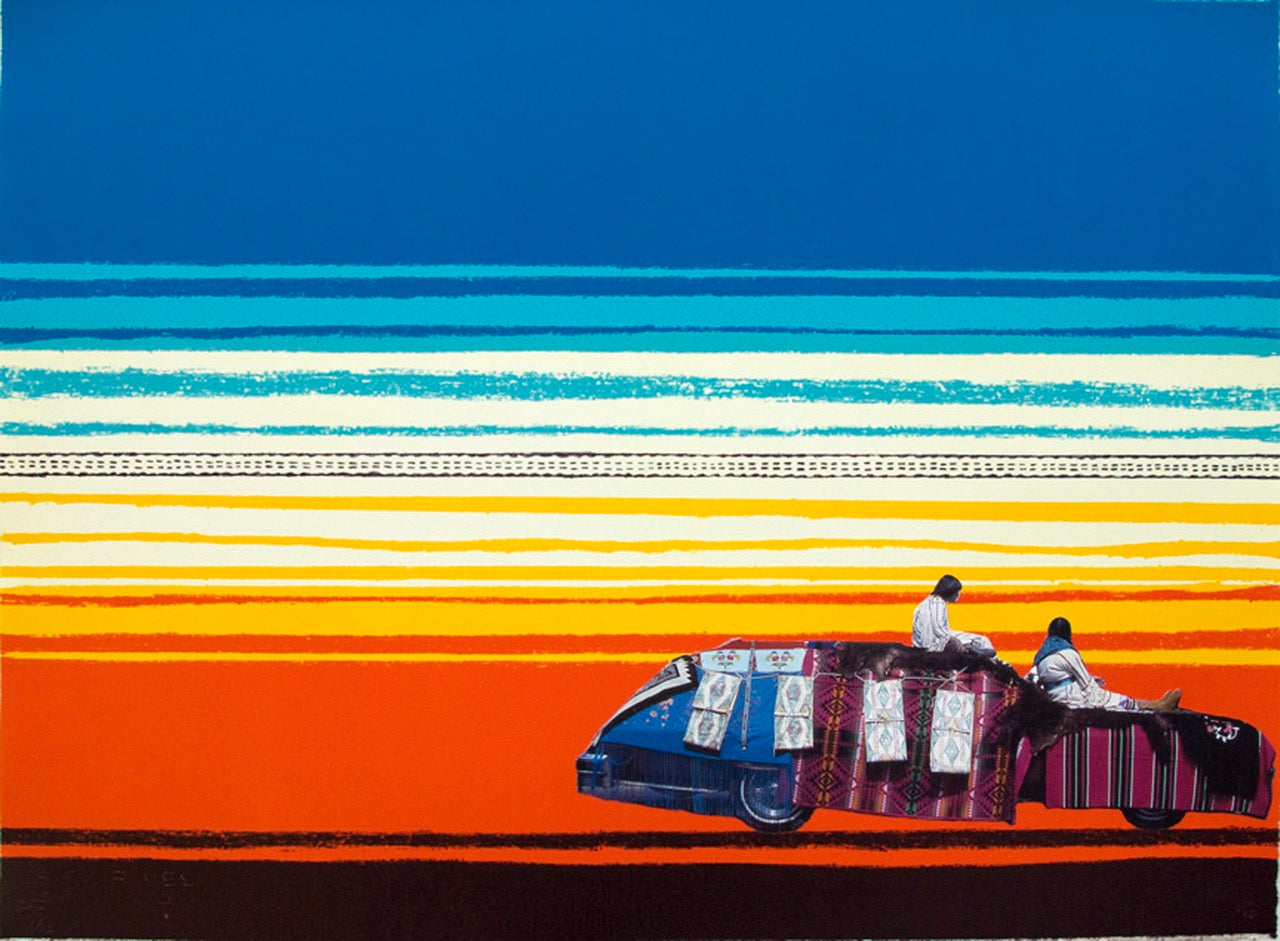

Wendy Red Star, 'enit,' 2010. Lithograph 10 of 101. Courtesy of The Gorman Museum of Native American Art

Room to Grow

The Gorman Museum, which is also celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, has always been committed to contemporary Native American art. The collection includes roughly 2,200 artworks, most created since 1980.

That may not seem like a lot for a museum, but it’s a 10-fold increase from when executive director Veronica Passalaqua arrived there in 2004. Working alongside Tsinhnahjinnie, the pair was able to use the promise of a new building to increase their collecting.

“When we knew this building was on the horizon, which was at our 40th anniversary, then we were able to start saying yes to accepting gifts,” Passalaqua explains of the collection’s growth. “In the past, there was no way that we could responsibly accept gifts into the collection because we just did not have the facility for it. All of the pieces we did collect were very tightly within our mission, but when we knew this was on the horizon, we were able to expand and include pottery and basketry and things outside our (emphasis of) works on paper.”

Collection items now include paintings, photography, ceramics, textiles and original prints from artists across North America including major-name figures like Rick Bartow (Mad River band of the Wiyot Tribe; 1946 – 2016), Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Dakota; 1915–1983), George Morrison (Ojibwe; 1919–2000), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation; b. 1940) and Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee; b. 1945).

“We’re proud of the collections we've built and we wanted to be able to have those out, like a museum, so people could engage with the collections and give depth to the contemporary work,” Passalaqua said. “So, if they go in the back, they'll see cases filled with pottery and maybe they're seeing something that resonates with the contemporary work in the front – ‘oh, hey, I see where that's coming from.’ It works together to be able to have these (historic) pieces, but that's not our focus, our focus is contemporary work, but we did want to expand it so visitors could get a deeper sense of the field.”

The Country Comes Around

Despite its small stature, the Gorman has a proud tradition at the vanguard of contemporary Native American art. Fifty years ago, the genre had little institutional or collector interest. Today, it’s firmly in the mainstream.

Through those long years of climbing, the Gorman was instrumental in pushing forward the careers of dozens of contemporary Native artists, offering them solo exhibitions, often their first museum shows. In the 1970s, the museum hosted the work Harry Fonseca (Nisenan, Maidu, Native Hawaiian, Portuguese; 1946–2006), Jean LaMarr (Susanville Indian Rancheria; b. 1945), Linda Lomahaftewa (Hopi, Choctaw; b. 1947), and Morrison, early presentations for artists who would become icons.

“We’re known for our solo shows and we still have that reputation in the Native art world,” Passalaqua said. “We’ve never sold work and we’ve never had a lot of money to pay people, but solo shows are needed. All artists need solo shows to advance their careers and so the Gorman was able to provide that for people.”

Gorman Museum of Native American Art at UC Davis exterior. Courtesy of the museum

For reopening, the Gorman’s temporary exhibition takes a group approach with “Contemporary California Native Art” featuring about 40 works by 20 artists, all members of California tribes, Bartow, Fonseca, James Luna (Luiseño, Puyukitchum, Ipai, and Mexican; 1950–2018) and Cara Romero (Chemehuevi Indian Tribe; b. 1977) among them. The show runs through January 26, 2024.

Prior to European contact, there were about 500 tribes in California, which has the largest population of Native Americans — about 760,000 — of any state. That reality, the California Genocide, the Land Back Movement, a recent wave of acknowledgement in the Golden State and nationwide about Indigenous contributions and atrocities those populations faced have placed the Gorman and its collection in a newfound spotlight.

“The political climate we’re in now is fortuitous for the museum, but that’s not where we were when we got the museum (approved),” Passalaqua said. “First it was Black Lives Matter and then it was a little more focus on Native America. We started getting land acknowledgment statements, more committees started being developed on campus, and then more attention in the outside world to Native art. We were promised this building 10 years ago, so this predates that.”

What the country, the state and the campus have finally found fashionable, the Gorman has been championing for a half century with the best yet to come.