Oscar Edmund Berninghaus (1874-1952) Biography

When Oscar Berninghaus succumbed to the effects of a crippling heart attack on April 27, 1952, a certain period of Southwestern Art effectively ended with him. One of the leading figures of the Taos Society of Artists and an artist whose success was hard-won, his passing represented the beginning of the end for the original painters of Taos and New Mexico. At 77, he was one of the elder statesmen of the New Mexico art community, whose body of work, in the words of artist Rebecca James, was "a magnificent document of the Southwest, painted as no one else has put down in this country. It is suffused with tenderness, is straight and tough as a pine tree, strong as a verb.”

Born in 1874 in St. Louis, "The Gateway to the West," Berninghaus would not have been a likely candidate for laureate of an important American art movement. At 16, he began working in a printing house in St. Louis, where he learned the technical skills required to make lithographs and engravings. At the same time he was working there, he was also attending night classes at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts, trying to improve his own artistic skills to a level where he could produce rather than process the commercial work handled in the printing shop. The School of Fine Arts led to the more prestigious Washington University in St. Louis and, in 1899, Berninghaus received his first major commission, a series of pieces for the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad's travel literature for New Mexico and Colorado.

On his way south from Alamosa to Sante Fe, Berninghaus made a friend who would turn out to be an important friend and ally for him later in life: Bert Geer Phillips. Phillips convinced Berninghaus to travel with him to Taos. Phillips had discovered Taos accidentally during an aborted trip to Mexico with Ernest Blumenschein the year before, and was still in the process of recruiting other artists to come and paint the landscapes of people of the region. While Berninghaus stayed only a week in Taos the first time, it was the beginning of a fruitful relationship, as he would spend incrementally more time there every year for the next quarter century, before moving there permanently in 1925.

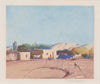

The light and landscape of the region captivated Berninghaus and, even when wintering in St. Louis, the sights and scenes of Taos were his primary subject matter. This ability to paint what he could not see in front of him, as he did when painting Taos natives from his studio, was both an intellectual conceit and a hard-earned talent picked up on sketching trips. Berninghaus believed that art was an emotional exercise, not a representational one. "The painter must first see his picture as paint-as color-as form-and not as a landscape or a figure. He must see with his inner eye, then paint with feeling, not with seeing." Tp this effect, Berninghaus took liberties with color and form in his pieces, omitting details when he desired and painting impressionist riffs on the landscape in the background at times.

In 1915, Berninghaus became a founding member of the Taos Society of Artists, one of the most important formal groups of American artists ever. Along with Berninghaus, Phillips, Blumenschein, Buck Dunton, E.I. Couse and J.H. Sharp all joined this group, whose aim was to market their artwork in traveling exhibitions, as there were no galleries in Taos to sell their work at the time. The traveling shows were a great success, and galleries in many American cities drew significant crowds to the work of these artists, whose combination of technical, academic skill and a sympathetic approach to the exotic people and landscapes of New Mexico were of great interest to the urban populace of the day.

It was also a financial boon to many of the Taos artists, who were able to sell many paintings to railroads, travel companies and large corporations in order to fund their fine art endeavors. Berninghaus was lucky enough to have a major account with Anheuser-Busch, whose steady patronage was a great help to him economically, allowing him to rent space in two different cities and, eventually, to move out of St. Louis entirely.

His relationship with the Pueblo Indians in the area was also a crucial element of his success. He had access to the Pueblo above and beyond almost every other artist in the area. He had a number of true friends within the Taos Indian community and was actually allowed within the kivas of the Pueblo, an honor usually not extended to white men. In exchange for access, the Taos Indians had a degree of control over Berninghaus' compositions, allowing him to paint the dances and rituals they felt it was appropriate to reproduce.

Berninghaus lived year-round in Taos for twenty-seven years, painting hundreds of pictures of the mountains, forests and people of the area. By the end of his career, he was able to paint without visual aids, creating portraits of people long since aged or dead from memory. He died in 1952, leaving behind a body of work that is much sought-after today.